This article originally appeared in IF Magazine #148 (August-September 2012).

It was 1982 and storyboard artist David Russell was tired of working in children’s animation. He expressed his ennui to close friend (and legendary science fiction author) Jack Vance and before long, he found himself on a plane to Los Angeles. Vance, who was negotiating the option to one of his novels with George Lucas, had scored Russell a job interview with Lucasfilm. One thing led to another and before long, Russell had a job as a storyboard artist on Star Wars: Return of the Jedi.

“Walking into Lucasfilm on that very first day was like walking into the Emerald City of Oz,” recalls Russell. “It was a stunning and wonderfully creative period.”

Since then, the storyboard artist and concept illustrator, who is now based in Queensland, has worked on more than 80 films with everyone from Steven Spielberg (on The Color Purple), Tim Burton (Batman) and Peter Weir (Master and Commander) to Baz Luhrmann (Moulin Rouge) and Alex Proyas (on the now-scrapped Paradise Lost).

In the digital age, it is surprising to learn that around 85 per cent of storyboards are still hand-drawn – and while this may seem obsolete in a world of green screens and computer-generated imagery, Russell says stories must be mapped out on paper long before any special effects can be put in place.

“When there’s an exceedingly complicated film where the entire world has to be created, all that has to be planned on paper first,” he says.

This was certainly the case for Paradise Lost, which was cancelled back in February when the studio was unable to deflate the budget to $120 million.

“Alex Proyas’ vision for the film was like nothing I’ve ever seen before,” Russell says. “The war in heaven, the ruin of civilisation, the look of the angels, the power of creation and the story of Adam and Eve were remarkably visionary and would have left an indelible image in an audience’s minds. It was a great tragedy the film did not go forward.”

Depending on the size of the budget, most films employ between one and three storyboard artists. The artists are contacted very early in a project’s development – sometimes even before the film has been greenlit, particularly when the story contains complicated key sequences.

Storyboarding for a typical movie takes about three months.

“Your job is to draw the strongest film possible and you’ll do that based on the director’s instructions and your own knowledge of filmmaking,” says Russell. “It’s very gratifying to see the sequences that you designed are there on the screen, sometimes with input from the director and sometimes without it.”

Storyboarding often overlaps with concept illustration – which involves creating detailed full colour portraits of important moments – although work in the latter area is most often completed digitally.

But it is not just defining scenes that the artists are responsible for; they are also often called upon to design hardware like weapons and vehicles.

Though Russell draws inspiration from European artists including Rubens and Caravaggio, he cites Marvel comic book artist Jack Kirby as his biggest influence. (Russell recently completed the storyboards for The Avengers computer game based on the film.)

“Most of the major film directors are quite aware and take cues from the best comic book artists,” he says. “It’s easy to see why – they are narrative, progressive art forms. Our best artists are coming from comic books and also the games industry.”

Russell recently completed storyboards for The Wolverine, which is currently shooting in Sydney.

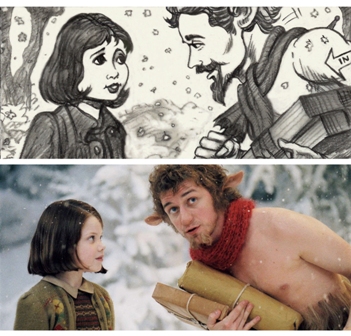

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and the way it appeared in the final film.