While local content makes up a small proportion of the Australian Netflix catalogue, Netflix has also heavily promoted Australian shows overseas, such as Hannah Gadsby’s standup show ‘Nanette’. (Photo: Ben King)

Over the last few years we have been studying the catalogues of Netflix and Stan to see how much local screen content each service carries and how this compares to international benchmarks.

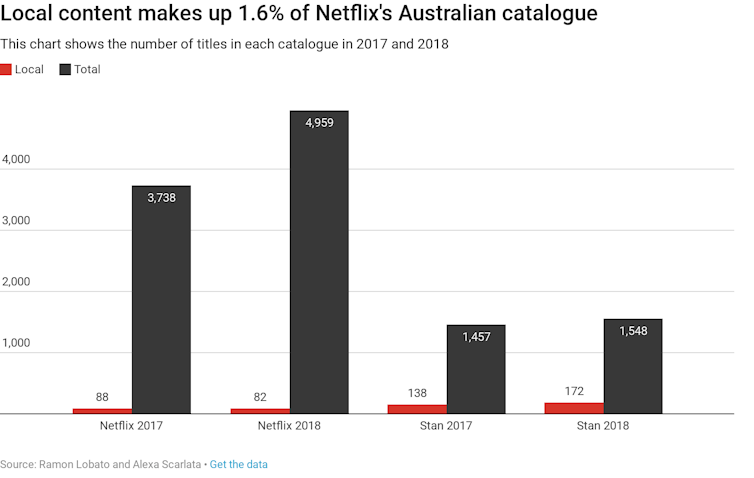

Our first report in 2017 found that the Netflix Australia catalogue carried around 2-2.5 per cent local content, much of it licensed from the ABC. Stan’s local content level was slightly higher, at 9.5 per cent.

Our latest report finds that Netflix’s local content level has fallen to 1.6 per cent (82 Australian titles out of 4,959). This is due to Netflix’s overall catalogue growth, rather than any significant decrease in the absolute number of Australian titles available. Stan’s local content level has risen to 11.1 per cent (172 titles out of 1,548).

While these figures may seem alarming, we should remember that, unlike free-to-air TV, subscription video-on-demand services are not regulated for local content. Netflix also plays a big role in promoting Australian content overseas.

Behind the figures

Digital access to local content, particularly on services like Netflix, has become a big issue for policymakers around the world. The European Parliament recently approved a minimum 30 per cent European content quota for video-on-demand services operating in the region.

In Australia, groups such as Screen Producers Australia and APRA AMCOS (a music rights organisation) are calling for new regulation to be introduced here. This could include local production spending requirements for video streaming services, or playlist quotas for music streaming services.

In this context, Netflix’s 1.6 per cent local content ratio might seem alarming, especially when compared to the minimum 55 per cent local content quotas that apply to free-to-air television in prime-time hours. But there’s more to the story. Comparing free-to-air TV and video streaming services is like comparing apples and oranges: one is regulated for local content while the other is not.

Netflix’s local content figures are arguably more in line with other parts of the screen industry. On pay-TV channels, where a local content expenditure requirement rather than an hours quota applies, local content levels are generally lower. At the local cinema box office, Australian films have historically made up around 9 per cent of releases and 4 per cent of takings.

Australia has long been an importer of screen content, and subscription video streaming simply extends that tradition into the digital age.

The changing TV ecology

Another way to approach the problem is to think about such services as part of a wider audiovisual ecology, with some parts regulated for local content and others not. Despite all the hype about the streaming revolution, Netflix and Stan do not simply replace free-to-air TV; they complement and interact with it.

Our research found, for example, that the ABC remains a very important supplier to both Netflix and Stan. Almost 60 per cent of the licensed local television content on Netflix and 37 per cent of the local television content on Stan was initially commissioned and distributed by the ABC.

The algorithms that determine how content is displayed to viewers on streaming services also complicate things. Users of Stan and Netflix experience the catalogue as a curated, personalised library rather than as a raw list. Hence, the visibility of Australian content in each portal will vary from user to user, depending on viewing history.

The bright side

There is a bright side to this story. Our research also looked at the availability of Australian content in Netflix’s international catalogues. We found, for example, that Netflix’s US catalogue contains more Australian content than the Australian Netflix catalogue does (both in the number of titles and the overall proportion of the library).

What’s more, Netflix markets a number of its Australian co-productions and exclusive acquisitions as Netflix originals in international territories, even though these are not available in the Australian Netflix catalogue (because the local co-production partners and commissioners typically have exclusivity).

So, the low levels of local content in the Australian catalogue must be considered alongside Netflix’s significant capacity to distribute and promote Australian content internationally.

What do the platforms have to say?

We invited both Stan and Netflix to check our figures. Netflix’s global public policy manager, Josh Korn, responded and provided some interesting context.

Emphasising Netflix’s international distribution function, Korn confirmed that Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette – Netflix’s first Australian stand-up original title – had been viewed by Netflix subscribers in over 190 territories. Similarly, he noted that 95 per cent of Netflix viewing hours for the Australian kids show, Mako Mermaids: An H20 Adventure, were from outside Australia, with similar numbers claimed for the dramas Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries and Glitch.

Netflix also points to the Australian shows in its production pipeline, including Pine Gap, Tidelands, Motown Magic, an untitled Chris Lilley project, and live stand-up comedy performances by Joel Creasey and Nazeem Hussein.

Stan, which was the first streaming video platform to commission local original content, has also recently released a new Romper Stomper reboot and its first feature, The Second, which add to the service’s existing Australian originals (such as No Activity, The Other Guy and Wolf Creek). New drama series Bloom and The Gloaming are in production.

This is all good news for Australian screen producers, who now have a bigger pool of buyers and new sources of production finance. But adding these new productions to both catalogues is unlikely to significantly increase the overall local content ratio in each service.

We may need to come to terms with the fact that Netflix and Stan cannot do the job of broadcast television when it comes to local content.

Ramon Lobato, Senior research fellow, RMIT University and Alexa Scarlata, PhD Candidate in Television Studies, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.