This week, actors such as Simon Baker, Bryan Brown and Marta Dusseldorp were in Canberra. Their aim was to convince parliament to introduce rules requiring streaming services such as Netflix and Disney+ to spend 20 per cent of their local revenue on new Australian drama, documentary and children’s content.

Many of Australia’s film and television organisations see local content rules as a key way of tackling significant changes that have disrupted business norms and revenue streams. The Federal Government has indicated it supports quotas for some services at least.

Requirements on global services seem an easy answer — and who doesn’t want more Australian TV? — but this call ignores complex realities of how the TV business and its funding have changed.

Before exploring the key differences of 21st century television, let’s consider why pursuing content requirements on streaming services is a high risk, low reward campaign.

1. Global streamers could leave Australia

Aggressively pursuing local content expenditure or special “taxes” may lead global streamers to cease Australian operation, risking a replay of last month’s Facebook fiasco in response to the overreach of the mandatory bargaining code.

Global streamers are precisely that: services making a business of circulating content globally, not producing it for all countries with subscribers.

Netflix, for instance, is now in roughly 60 per cent of Australian homes. Yet those 6 million subscribers amount to less than 3 per cent of its total subscriber base. At some point, the cost of producing content for such a small part of a service’s subscriber base becomes unfeasible from a business perspective.

2. New services might not come to Australia

Australia has consistently been one of the first markets entered by new streaming services — our low adoption of cable TV means we are hungry for more video options.

Although much attention focuses on Netflix and Disney+, several smaller global services such as Acorn, Britbox, and Discovery+ are also available here. Many of these offer a particular kind of programming, drama and mysteries in the case of Acorn, and British series for Britbox.

Creating Australian content is contrary to the business of these services. Rules requiring local content will discourage the next stage of streamers offering more specialised services from launching here, leaving Australians with less choice — VPNs notwithstanding.

3. Netflix could become more like Stan, reducing Stan’s key value proposition

A curious part of the plan for local content requirements on streamers proposed in the Federal Government’s media reform green paper is that Australian content requirements would apply to global streamers but not Stan.

Stan reported 2.2 million subscribers in 2020, roughly 22 per cent of Australian households. Stan offers more Australian content than any other streamer. Last year, 7.38 per cent of its library was Australian programs – although this is a decline on 2019 when the figure was 9 per cent.

Offering a substantial amount of Australian content makes sense for a domestic service and distinguishes Stan from global providers. According to the government’s Media Content Consumption Survey, commissioned in November 2020, Stan is the second most subscribed service in Australia behind Netflix.

However, if global streamers are forced to make Australian content, they become more direct competitors, potentially eroding Stan’s point of difference.

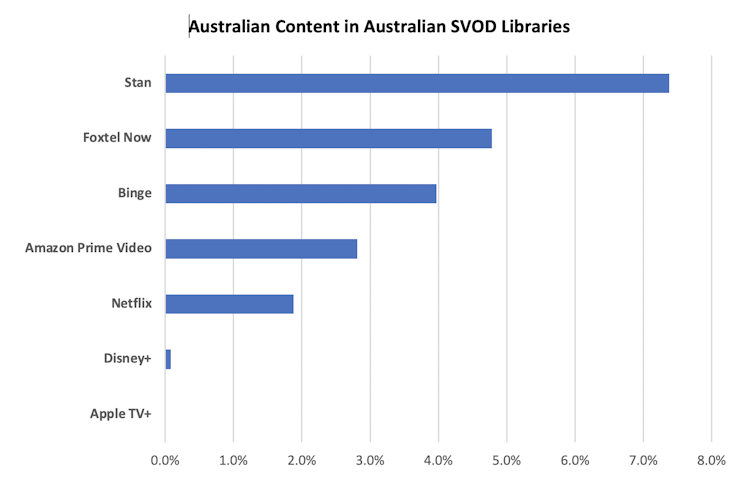

Recent data from Ampere Analysis shows the percentage of Australian titles in Australia’s six most subscribed services (plus newcomer Binge). Stan leads, followed by Foxtel Now (just under 5 per cent), Binge, Amazon Prime, Netflix and Disney+.

Unsurprisingly, Australian services have more Australian content than global ones, but less than domestic services in other countries. Most of the titles included here were originally created for television or cinemas so only account for new production activity in a few cases. Stan’s library includes 20 Australian commissions, less than 1 per cent of its offerings.

Still, it makes no sense to exempt Stan from local content requirements. As an Australia-only service, 100 per cent of Stan’s reason for being is to provide content for the Australian market, while for the global services, providing content for Australians is 3 per cent or less of their business.

4. Global streamers are likely to make programs in Australia but not about Australia

Global streamers aren’t likely to make content that is very Australian. They need stories with universal legibility.

Consider the Australian titles produced to date by Netflix such as Tidelands and children’s drama The New Legends of Monkey. Was Tidelands, with its story of mythical part-human, part siren Tidelanders, one that resonated with the fabric of Australian culture?

Despite the rhetoric of Australian stories, this industry campaign is chiefly about jobs. It is about securing new sources of funding for Australian productions in response to commercial broadcasters struggling with diminished advertiser spending. Industry subsidies in the face of such change may be warranted, but effective policy solutions must deal separately with the issues of sector support and cultural policy — such as the need to tell Australian stories.

Let us be very clear, we care a lot about the future of Australian stories. We are deeply concerned with the many policy developments of the last two decades that have allowed industry priorities to subordinate the cultural goals of ensuring Australians see themselves and their lives reflected on screen.

But Australia needs 21st century policy solutions that reflect the contemporary media landscape.

Complex realities

Streamers aren’t broadcasters. They are paid for by subscribers, not advertisers. They do not use public spectrum, which is a basis of local content requirements on broadcasters. A more direct analogue with streamers is the video rental store, which never faced requirements to offer Australian content.

Global streamers are a part of the marketplace viewers find valuable enough to pay for, but they aren’t the cause of the faltering Australian TV industry. The problem there — much like for print journalism — is that advertisers have found more effective ways to reach potential consumers.

Netflix reports that it accounts for 10 per cent of viewing in the US, that’s far from dominance or crowding out others. The new video marketplace is complicated and offers Australians more choice — but global streamers can’t save Australian television.

Amanda Lotz, Professor of Media Studies, Queensland University of Technology and Anna Potter, Associate Professor, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.