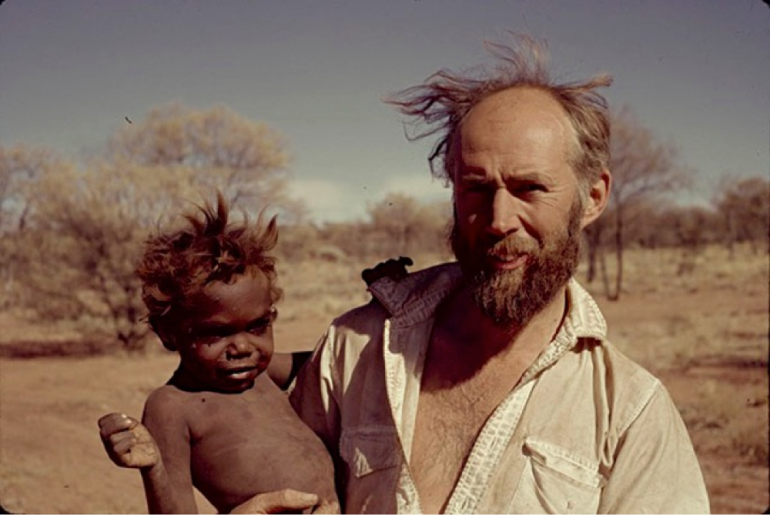

Australia lost a pioneering documentary filmmaker this week with the passing of Ian Dunlop in Canberra. A friend and colleague, Ian’s People of the Western Desert, begun in 1965 and comprising 19 films, was a landmark in the history of international documentary. The series of films won international acclaim. In 1967, Ian edited a cinema release version of the series which won even greater acclaim, including the prestigious Gold Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and was screened throughout the world.

Ian Dunlop began making films for the Commonwealth Film Unit in the late 1950s. I had the good fortune to meet Ian in the corridors of the CFU’s successor, Film Australia, in the mid-1990s when I was directing Mabo Life of an Island Man with producer/editor Denise Haslem. Ian was collating and cataloguing his enormous collection of films and production stills so they could be archived. Some of his work was going to the National Archives of Australia and some to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. We became good friends. My wife Rose Hesp and I would share many meals at Ian and Roey’s place on the edge of the bush in Gordon. Their beautiful mid-20th century minimalist wood and glass home housed a treasure trove of art works from Papua New Guinea and north-east Arnhem land. We also shared with Ian and Roey a passion for Italian red wines.

In the early 2000s Ian, Denise and I collaborated on a project together, Ceremony: The Djungguwan of Northeast Arnhem Land, produced in collaboration with, and at the request of, the Yirrkala Dhanbul Community Association and the Rirratjingu Association for Film Australia.

Like a ‘grand opera’ the ‘Djungguwan’ is an initiation ceremony of the Rirratjingu and Marrakula clans. It teaches young boys about discipline, law and respect for Yolngu traditions. A ceremony of transition, teaching and remembering, it can take weeks to stage and perform. The Yolngu’s ‘Djungguwan’ has a unique place in Australian cinematic history. It’s been filmed in its entirety on four separate occasions.

In 1963 the ceremony was first documented on film by anthropologist Nic Peterson for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Ian filmed the ceremony for Film Australia in 1976 with the great, then observational documentary DOP, Dean Semler. Denise, Rose and myself similarly recorded it the ceremony in 2002 in Yirrkala. In 2003, the ceremony was once again staged at Gurka’wuy and filmed by Kos Tambling.

The result of our collaboration with Ian was a DVD set comprising a three-hour version of the “Djungguwan” filmed by him in the mid-70s, and a 75-minute version directed by myself in 2002.

One of the great experiences Denise, Rose and I, along with our young daughter Angelita, had in our ten months living and filming in north-east Arnhem land was watching Ian Dunlop’s Yirrkala Film Project with the Yolngu. It comprises 22 films, each are around 60 minutes in duration. Our living room became an impromptu theatrette as dozens of family members dropped by and stayed for hours transfixed by the intricate preparations and ritual dances flickering on our TV screen. Their reverence was sometimes punctuated by tears and hoots of laughter. Ian’s films may be a priceless record of the oldest continuous culture on Earth, but for the Yolngu they are also ‘home movies’ in which parents, grandparents and extended clan members are lovingly remembered, immortalised on film performing one of their most important sacred rituals.

One of Ian’s closest Yolngu collaborators during his time at Yirrkala in the 1970s was Mithili Wanambi, an esteemed clan leader and artist. He instantly understood the importance of Ian’s work and fully embraced and supported his film project. Almost 30 years later, because of our friendship with Ian, we were welcomed by the Yolngu. He was a legendary figure in their eyes. He had documented their life at a time when Indigenous culture barely mattered to white Australia. He was loved and respected by their elders, and revered by their descendants. A friend of Ian’s was a friend of the Yolngu. Thus our consultant/translator became Mithili’s son, Wukun Wanambi. As the oldest male child of Ian’s lead consultant, Wukun adopted us into his family and his kinship line. We spent weeks and months with Wukun, and many, many hours with he and his family, watching Ian’s films as they pointed out relatives and explained the stages of the ceremony. Today Wukun is a highly acclaimed Arnhem Land painter, sculptor and video artist who uses his art to advocate for a true understanding of Aboriginal culture.

The Ceremony – Djungguwan DVDs were launched by Film Australia to mark UNESCO World Day for Audio Visual Heritage and presented to their collection in 2007. The documentaries featured in the set are cultural crown jewels: a priceless part of Australia’s heritage made with and for the Yolngu for future generations.

Ian Dunlop will never be as well-known as film directors like George Miller, Peter Weir or Gillian Armstrong, but he has left a legacy to Australia’s cultural and filmmaking heritage every bit as important, and one that may well stand the longer test of time.

As Wukun Wanambi says in the Ceremony Djungguwan: “So this is now for the future generations. Dhuwa and Yirritja so that you can see this picture and remember what we are doing”.

Ian’s films will live on, but he will be greatly missed.