People with disability working in the screen industry routinely experience prejudice, are lower paid, offered more precarious work and are in less powerful positions than their non-disabled counterparts.

These are some of the top line findings from a new University of Melbourne report, Disability and Screen Work In Australia, based on a survey of 257 disabled and 252 non-disabled screen workers and in-depth interviews, conducted in partnership with the Melbourne Disability Institute and production company A2K Media.

The report found the screen industry needs widespread structural, attitudinal and cultural change in order to become more inclusive.

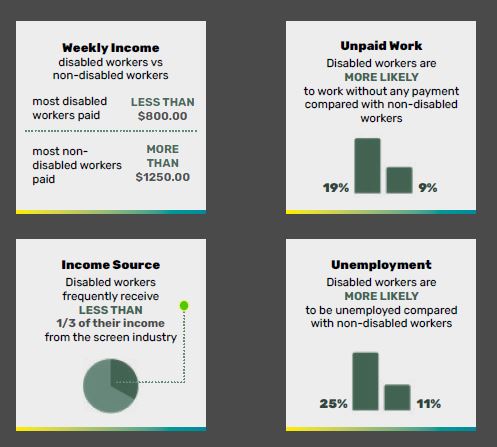

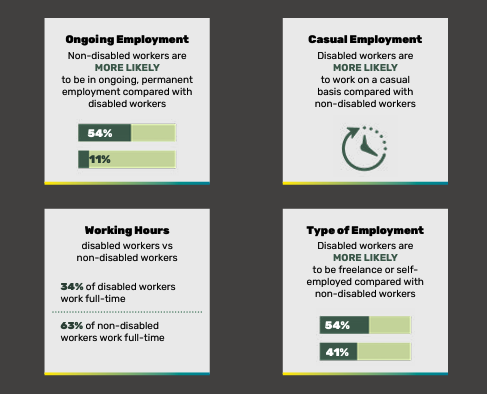

On the issue of pay, a majority of disabled screen workers earn less than $800 per week, while most non-disabled screen workers earn more than $1,250. People with disability are also more likely to be employed on short-term contracts, to perform unpaid work or to be unemployed.

Almost 40 per cent of respondents with disability recalled at least one unpleasant experience at work related to their disability status in the last 12 months, including being insulted, threatened or excluded. Common examples included jokes about disability and meetings held without regard for access requirements.

Interviewees who had worked in other areas of the economy found disability and inclusion support was “markedly” better in other industries compared to the screen sector.

In particular, the report notes the screen sector is often inflexible for those who may require rest breaks or time off for symptom management, with the image of a successful screen worker one who “amasses a list of credits at breakneck speed.” Documentary filmmaking was regarded as more flexible than scripted film and television production.

“The industry’s work culture sometimes prizes extremes conditions and frowns upon necessary supports such as sick leave,” the report states.

“Employment structures and practices often lack mechanisms that are common in other industries, including workplace inductions and human resource staff. The nature of creative work can make people feel more personally involved and vulnerable. Some respondents and interviewees suggest that this exceptionalism is used as an excuse by screen workers for the screen industry’s inflexibility and inaccessibility.”

Accessibility issues were reported not only in production and post-production spaces, but at networking events, conferences and festivals.

The report also found that people with disability found talking about their disability status at work dangerous and stressful. Some 47 per cent of respondents only sometimes revealed their disability status, and 24 per cent of respondents never did. Further, while 79 per cent of non-disabled workers reported their colleagues were willing to or very willing to work along disabled people, only 49 per cent of disabled workers reported the same.

“What came up repeatedly in our research was the discriminatory attitudes that disabled workers in the screen industry face, both from their colleagues and their bosses,” said lead research Dr Radha O’Meara.

“Disabled screen workers told us that practical issues could be solved relatively easily – and often at no extra cost – if their bosses and colleagues were willing to listen to them and work with them.”

However, almost half of screen workers with disability surveyed reported their lived experience also impacted their work in positive ways, including unique skills and perspectives.

Among the report’s recommendations are widespread participation in disability equity, accessibility and inclusion training; the normalisation of access requirement discussions, and the widespread use of Disability Action Plans.

It also suggests there needs to be greater dialogue between disabled screen workers, disabled-led organisations, government agencies, guilds and associations, and there needs to be greater creativity and flexibility in standard industry practice.

One of its key points is that greater flexibility in access and schedules would be beneficial for everyone.

“The screen industry is inaccessible for many non-disabled workers, too,” the report states.

“The long hours, inflexible schedules, tight deadlines and high stress levels are accepted as norms of screen work, but they make many roles inaccessible for a variety of workers, including disabled people parents and carers. Such conditions impede a sustainable work-life balance for all workers. The industry needs to focus on universal access.”

At a government level, the report recommends targeted funding to prioritise storytelling by and about people with disability, and for the support of the sustainable careers. It also suggests money be allocated for access requirements on all government funded projects, and funding streams be revised to support diverse career trajectories.

“Currently the screen industry entrenches social disadvantage, by excluding and marginalising disabled people. But disability can make our screen work better. What attracts Australian and international audiences is compelling, authentic storytelling – and only a film industry that represents a diverse range of experiences can deliver those stories,” said O’Meara.

“Disabled people have so much to contribute to the Australian screen industry. We need greater participation of disabled workers in the industry, and we need these people to be fully included – to be surrounded by colleagues and bosses who really value their contributions and will work with them in flexible ways so they can do their jobs well. The screen industry can only attract and retain the best talent if it’s accessible to disabled people.”

The results of the survey will inform partner A2K Media’s ambitions to deliver an online education platform via its Disability Justice Lens project.

A2K Media is co-founded by Ade Djajamihardja, who after a stroke in 2011, struggled to rejoin the screen industry where he had once had a successful career.

“I did not realise the extent of both discrimination and exclusion that I would be confronted with as a disabled screen professional. The industry was no longer accessible for me,” Djajamihardja said.

“The first five meetings I tried to attend, I could not even get in the door, let alone think about working again. I love this industry, so I dug deep and worked together with the A2K Media team to use this experience as motivation to make positive and progressive meaningful change.”

Late last year, preliminary data from the Screen Diversity and Inclusion Network’s Everyone Project found people with disability were vastly under-represented compared to the population benchmark (17.7 per cent), both on screen (8.9 per cent) and behind the camera (5.3 per cent).