Australian camera departments are whiter, older and overwhelmingly more male dominated than the general workforce. Bullying and discrimination on the job and in hiring are reportedly commonplace, and sexual harassment ‘routine’.

In addition to significantly outnumbering their female counterparts, male directors of photography consistently progress faster into technically demanding and creatively prestigious roles, have substantially longer careers and get paid more than women for the same types of projects. As budgets go up, the likelihood of a woman DOP being attached to a project decreases.

Further, a majority of the Australian camera professionals see workplace conditions, such as long hours, unpredictable schedules, competition for work, and job stress as impacting negatively on their wellbeing, and struggle for work/life balance. Many DOPs face chronic unemployment, income and wage insecurity.

These are some of the topline findings from the Australian Cinematographers Society’s (ACS) landmark A Wider Lens report, launched today, which has significant implications not only for camera departments but industry practices at large.

Conducted by researchers from Deakin Business School and Tallinn University, A Wider Lens is based on Screen Australia data of feature film and scripted TV production from 2011-2019, and the results of the ACS’s camera workforce survey, which received 640 responses.

It analyses the major factors which enable or constrain career pathways into cinematography, and experiences of camera professionals in recruitment and the workplace. The picture the findings paint is one of inequality, discrimination and a lack of diversity. It finds many workplace conditions, as well as commonplace bullying and discrimination, result in significant mental health consequences, to the point of threatening the industry’s long-term sustainability and growth.

Broadly, the researchers suggests there is an “industrial scale”, cross-industry effort required to address a toxic work culture. The reports lists some 19 recommendations for inclusive workforce growth, including around data collection and reporting, hiring practices, pay equity and industry programs to support work/life balance, safety and wellbeing.

In particular, it urges the majority of interventions need to focus on decision makers who control project finance, hiring and investment decisions.

While some of the country’s best known DOPs are women, including the Oscar-nominated Ari Wegner, Mandy Walker, Bonnie Elliott, Zoe White and Katie Milwright, the overall report suggests significant systemic barriers for the participation of women in the camera department. These also intersect with other significant barriers to do with age, class, ethno-cultural identity, sexuality, disability and caring responsibilities.

Speaking to IF, ACS national president Erika Addis – who formed the society’s Women’s Advisory Panel in 2012 – says the results of the report, while not surprising, are even worse than expected.

The ACS was driven to commission A Wider Lens initially in part as cinematographers and other heads of department have typically been left out of data collection and funding initiatives aimed at redressing inequality.

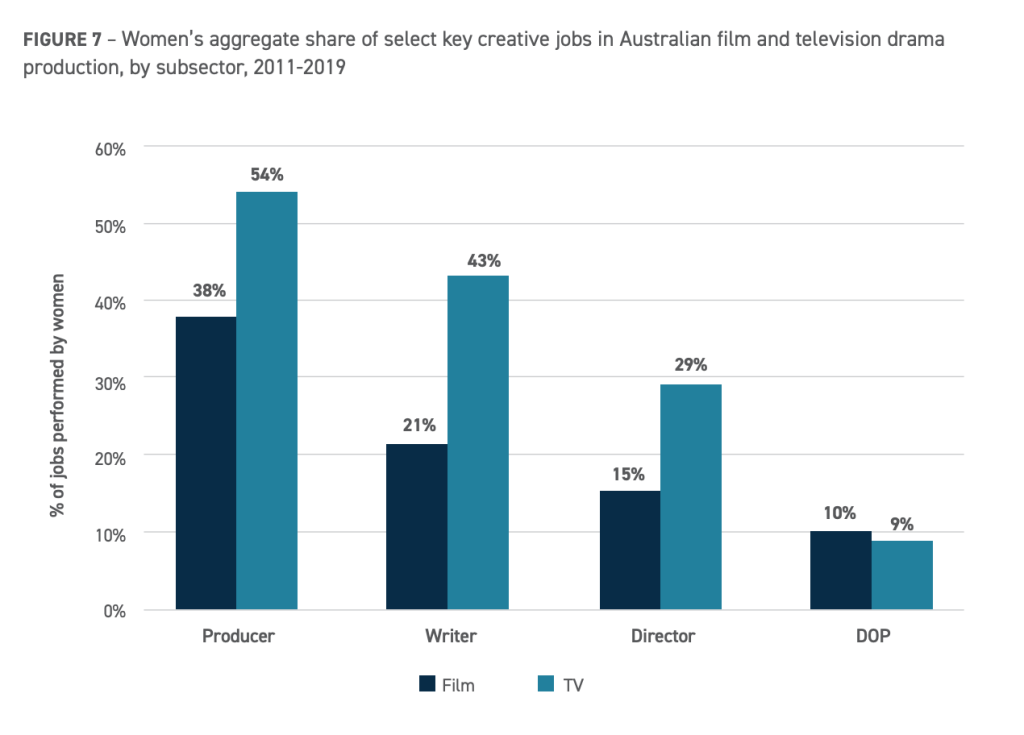

This includes Screen Australia’s Gender Matters, which has primarily focused on directors, writers and producers. However, as the report notes, cinematography is significantly more gender-imbalanced than any of those three key creative roles – in fact, a woman is three times more likely to have worked as a director on a feature film/scripted TV series than as a cinematographer.

More recently, Screen Australia has collaborated with the ACS and the Australian Guild of Screen Composers to create Credit Maker, an initiative aimed at boosting representation of female cinematographers and composers alongside directors.

However, heads of department are still not included in Screen Australia’s Gender Matters KPIs, something Addis hopes will change.

“In the current situation, where the numbers of women who are involved in projects as writers, producers and directors influences how projects get financed, we want heads of department to be counted too,” Addis says.

With the report touching on wide-reaching issues, Addis notes there is a significant body of work for the industry off its back, and will require collaboration across a variety of stakeholders, including government.

“It is a deep forensic investigation that we’ve provided… that absolutely needs to be taken up, extended and and not swept under the carpet.”

From the perspective of the ACS, she intends to lobby government agencies to consider HODs in their data collection, funding decisions and diversity initiatives; to work with unions and other guilds to push for pay transparency; and to advocate for wellbeing officers to be installed on productions.

What’s the make up of the camera department?

In terms of basic demographic info, 80 per cent of the camera workforce are men, 18 per cent women and 2 per are trans or gender diverse. Almost 70 per cent are over 35, and 68 per cent of Anglo-Celtic background and 36 per cent European. Approximately 8 per cent identify as having a disability and 17 per cent as LGBTIQ+.

Nearly half of all women in the camera workforce (47 per cent) are under 35, compared to just 28 per cent of men. Women were more than three times likely to identify as LGBTIQ+ and nearly twice as many women than men reported a non-European/Anglo-Celtic ethno-cultural identity.

Of those surveyed, only 1.7 per cent of DOPs identified as Indigenous men, and none as Indigenous women.

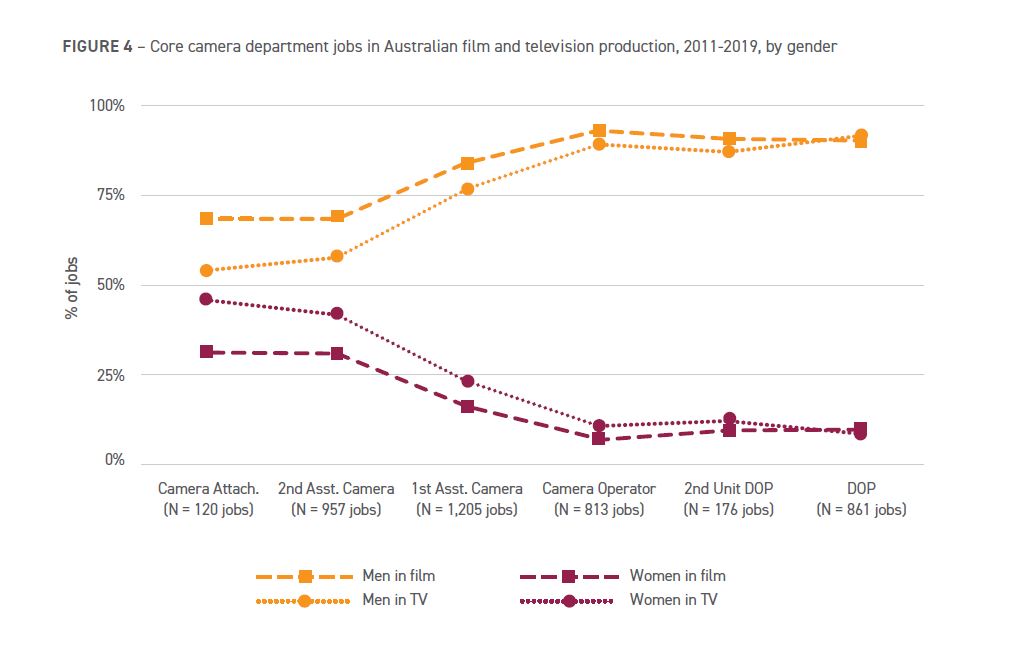

On film and scripted television shot across 2011-2019, 91 per cent of the 861 DOP roles were taken by men, and men outnumbered women in the camera department more generally 10 to 1. Of the 102 digital imaging technicians (DIT), 279 steadicam operators and 52 underwater DOPs employed across 2011-2019, not a single one was a woman.

However, the report suggests some change in the pipeline, in that women’s participation in core camera roles, such as 1st and 2nd ACs, improved across the period.

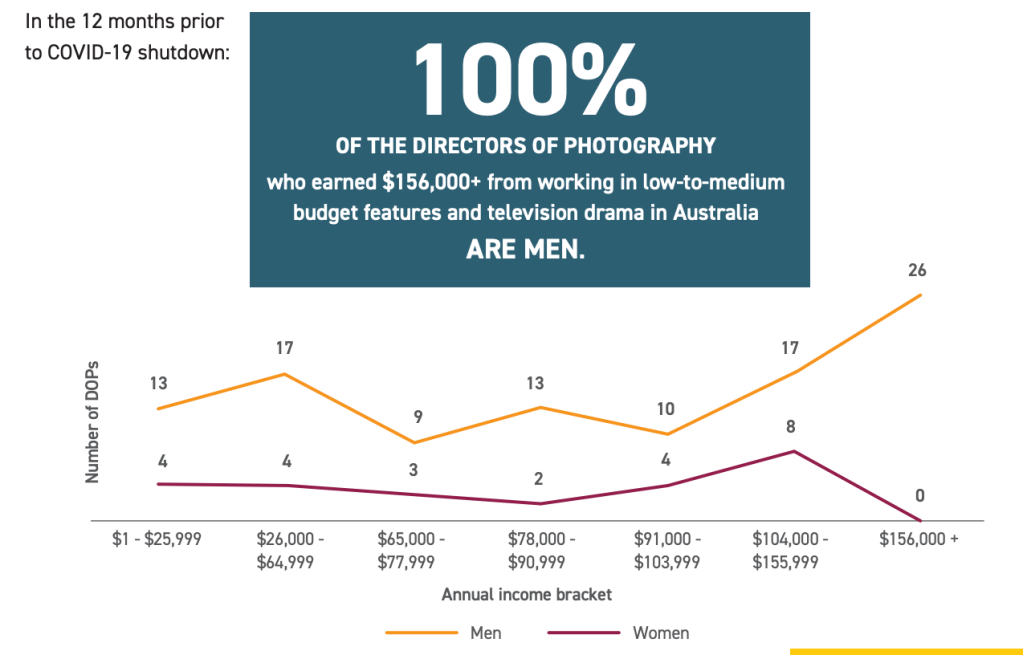

When women are employed as DOPs, it tends to be on lower budget features, or in TV. In the 12 months prior to the COVID shutdown, a woman was much less likely than a man to have worked on a film with a budget of more than $2 million, and men lensed all film with budgets over $US10 million.

There was also found to be a significant pay gap for women, which could not be explained by lack of experience or education.

With such marked inequity, among the report’s key recommendations is that DOPs are considered in workforce diversity strategies, and that efforts to improve gender diversity in the camera department focus the cinematographer as the key leadership role; women DOPs were 15 per cent more likely to hire other women.

Further, it recommends broadcasters, producers and financiers must “immediately implement” pay transparency on all film and TV production, and that the ACS publish a publicly available rate card. It also encourages all unions, guilds and professional associations to support a workforce-led pay transparency campaign.

Workplace conditions and hiring

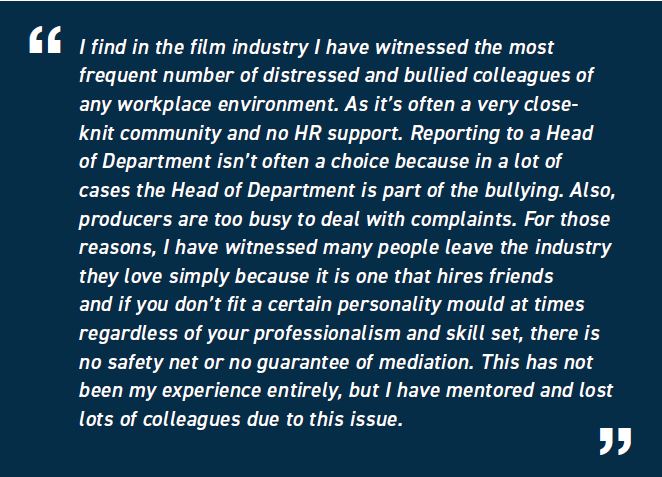

In terms of recruitment, 89 per cent of respondents reported word-of-mouth and social networks as the number one way they found work, with the report suggesting these networks are “reputation-based, self-referential and self-reinforcing.”

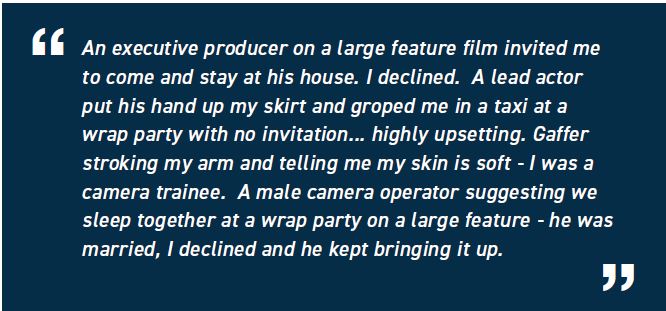

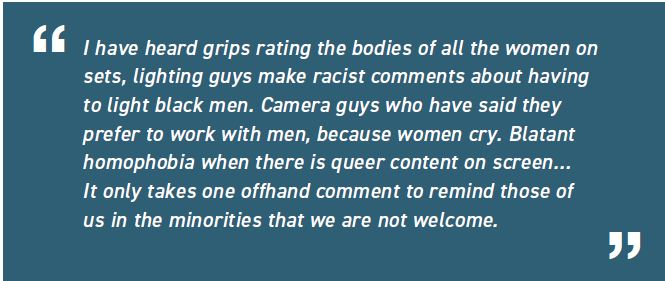

Half of the survey respondents reported discrimination in hiring or the workplace, including 89 per cent of women experiencing sexism, 62 per cent of people aged 56-64 ageism, and 50 per cent of both non-Europeans and Indigenous workers racism. The vast majority of respondents who experienced bullying, harassment and discrimination avoided reporting it in case it negatively impacted their careers. This included 100 per cent of all Indigenous respondents, 87 per cent of respondents with a disability, 84 per cent of women and 81 per of LGBTIQ+ respondents.

The report suggests the industry “urgently” needs a targeted, high-profile industry campaign to educate people about bullying, harassment and discrimination at work, and that compliance with the Australian Screen Industry Code of Practice on discrimination, harassment, sexual harassment and bullying should be a mandatory, rather than voluntary, condition of membership for Screen Producers Australia.

More broadly, it urges for programs that disrupt exclusionary hiring networks; the development of a centralised industry talent database specifically dedicated to the discovery of crews of equity-seeking background, and for work opportunities to be openly advertised.

In terms of workforce conditions, 60 per cent of respondents to the survey reported that work stress impacted their mental health, and the same proportion that work did not allow for balance in their personal lives. Some 42 per cent did not feel comfortable raising personal or family commitments in relation to work schedules.

These conditions also led to people leaving the industry, resulting in talent drain. In terms of women who no longer work in the camera department, 75 per cent reported factors due to the social/household impacts of work; 60 per cent interference with caring duties; and 57 cent per negative mental health impact.

The report recommends the industry look at flexible working and job sharing options, and that Raising Films Australia’s 2018 recommendations around childcare funding, incentives and return to work programs for parents/carers be revisited.

Reflecting on A Wider Lens, Wegner said: “For things to improve, we must first have a clear picture of the current situation – as confronting as that may be.

“This report offers some shocking statistics as well as tangible recommendations, which I hope will be heard and implemented. With our diverse population and history of creative talent, Australia is in a great position to be a world leader in transforming the film industry – if we choose to act.”

The executive summary of A Wider Lens can be found here.