Actor Tilda Cobham-Hervey and director Unjoo Moon on the set of ‘I Am Woman’.

While Screen Australia reports that 57 per cent of all key creatives to receive production and development funding last year were women or female-identifying people, new industry-wide data suggests bolstering women’s participation more broadly is a slow road.

In 2015, a set of stats sent a shockwave through the industry: For all Australian films released between 1970-71 and 2013-14, only 16 per cent of directors, 21 per cent of writers and 30 per cent of producers were female.

The Screen Australia research data, published in AFTRS’ Lumina magazine, was widely regarded as a wake-up call. It led to a chain reaction of initiatives from various organisations to bolster women’s participation in the screen industry, not least of which was Screen Australia’s own $5 million Gender Matters program and set of KPIs for its funded projects.

Yet, updated industry-wide data, released today by Screen Australia for the period 2015-16 through 2018-19, suggests change is slow coming.

In that four year timeframe, only 18 per cent of all Australian features were directed by a woman or female-identifying practitioner. Thirty-eight (38) per cent were produced by women, and 23 per cent written by women.

Television is a brighter picture, though for the most part, participation remains below parity. For the same period, 57 per cent of TV producers were women, but only 33 per cent of directors and 46 per cent of writers.

In doc, 51 per cent of producers were women, 37 per cent of directors and 41 per cent of writers.

The agency has also tried to track women’s participation in online formats for the first time. Often the digital arena, where there are fewer gatekeepers, is regarded as inherently more diverse. But while 63 per cent of producers were female, only 38 per cent of directors and 41 per cent of writers were women.

Screen Australia on track to meet KPIs

However, on Screen Australia-funded projects at least, women’s participation in key creative roles is edging far closer to parity.

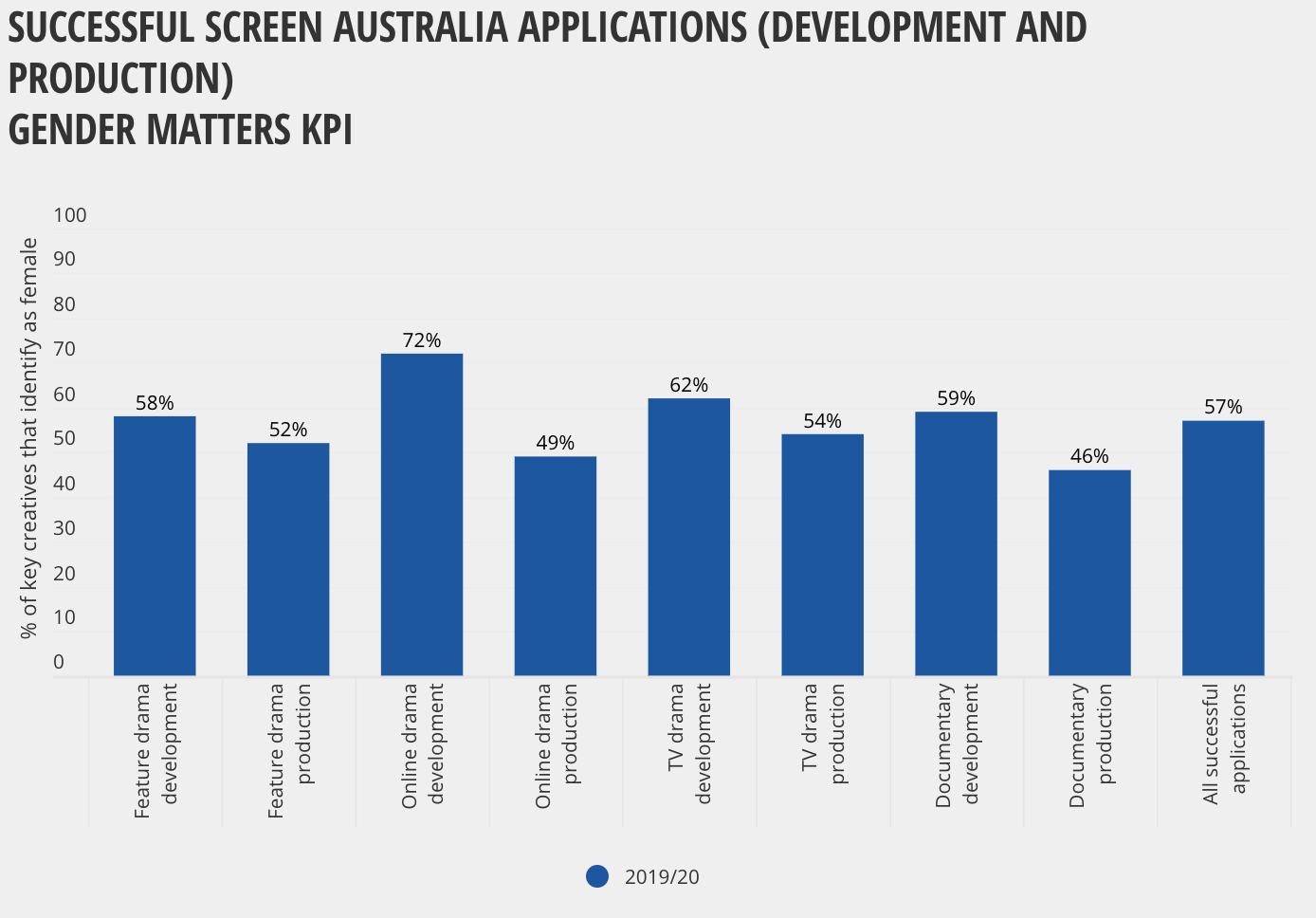

Last year, the agency set itself a new Gender Matters KPI: by 2021-22, 50 per cent of key creatives across all projects that receive both development and production funding should be women or female-identifying practitioners.

The agency believes it is on track to hit this, with 57 per cent of all writers, directors and producers meeting the criteria in 2019-20.

The new KPI sees Screen Australia track headcount for the first time. In previous years, it simply measured whether a project was ‘female-led’.

For chair of the Gender Matters taskforce and Screen Australia board member, producer Joanna Werner, the measure is not only more accurate, it also means there is “nowhere to hide”.

It’s also the first time the agency has collected data on development. For Werner, this is an important change.

“We want to make sure that women are represented at every stage of the project’s lifecycle, and not just potentially an afterthought or quota for inclusion when production stages are reached,” she tells IF.

For 2019-20, women made up the majority of the key creative roles in successful development applications across every format, with figures ranging from 58 per cent in feature film through to 72 per cent in online drama.

Yet there are early signs to suggest there may be barriers to female participation when projects move through to production, as the numbers drop off.

Successful applications in features and TV drama production saw women at 52 per cent and 54 per respectively in all key creative roles. However, documentary production was below parity at 46 per cent and online drama at 49 per cent.

However, these numbers are for the most part reflective of an upward trend when compared to previous years.

Significantly, 2019-20 marks the first time that women have represented more than 50 per cent of all key creative roles in successful feature film production applications to Screen Australia. Feature writers have increased from just 17 per cent in 2016-17 to 45 per cent in 2019-20, and directors from 10 per cent to 50 per cent over the same time period. Producers have gone from 40 per cent to 59 per cent.

However, whether this can be maintained in the future is a key question: Screen Australia notes that the increase in the numbers for this year in film can be in part attributed to counting two anthology features with multiple female creatives: Cook 2020: Our Right of Reply, and Here Out West.

For TV drama projects to receive production funding, women were above parity on every count, with female writers at 53 per cent, directors at 51 and producers at 61 per cent.

For Werner, the success in TV is part due to the fact that in 2018, Screen Australia made it a pre-condition of funding that for drama series with more than one block, one or more of those blocks would be directed by a woman.

For documentary projects to receive production funding in 2019-20, women were 55 per cent of producers and 43 per cent of writers, but just 37 per cent of directors. For online production, 51 per cent of producers were women, 42 per cent of directors and 52 per cent of writers.

It should be said that Screen Australia’s data for its funded projects is not directly comparable to the industry-wide data; it is measured differently. For instance, a female producer may have two projects approved for production funding in a financial year via Screen Australia, therefore be counted twice towards the agency’s KPI. Yet they would only be counted once in the industry-wide data, which is a count of individuals working in the industry.

Time for industry to “follow suit”

Members of the Gender Matters taskforce, top to bottom, L-R: Anusha Duray, Joanna Werner, Monique Keller, Lisa French, Sarah Bassiuoni, Tania Chambers, Rachel Okine, Deanne Weir, Fiona Tuomy, Meg O’Connell, Sophia Zachariou, Rosie Lourde, Liz Doran, Que Minh Luu, Kristy Matheson. (Photo: Daniel Boud)

While Screen Australia should lead by example when it comes to women’s participation, it’s also time for the industry at large to act, according to Werner.

“The industry-wide data is really interesting to look at,” Werner tells IF.

“You can see how much Screen Australia is doing the heavy lifting and leading the way. The industry really needs to follow suit.”

Werner would like to see production companies set self-imposed rules or take active steps to ensure they are considering women for all key roles on set.

“It’s incumbent on every production company to look at the make up of their crew and cast, not just if you’re required by Screen Australia.”

Looking at the industry as a whole is one of the aims of the 18-member Gender Matter Taskforce, which provides independent advice to the agency and looks beyond its direct sphere of influence.

It has this year identified three focus areas to bolster industry-wide efforts to gender parity: outreach and career progression, market and audience, and key roles and heads of department.

Werner is particularly focused on boosting female HODs and getting women in crew, “So often on location recce with all of the HODs, you’d be one of three women. It’s getting better but it’s certainly not at parity.”

Indeed, one of the criticisms of Screen Australia’s Gender Matters has been that is only focused on above-the-line.

Below-the-line, women are also heavily underrepresented. For instance, while the Australian Cinematographers Society (ACS) has made concerted gender and diversity efforts in recent years, just 16 of the 413 people to ever receive accreditation have been women.

“It’s looking at the grassroots,” says Werner. “How do you encourage women to take a leap to working in the film industry? How do we support them through the lifecycle of their career, whether coming back to after work after having a child or supporting women to still be able to have a career through particular times of their lives? And then supporting them to take the next steps up, so that when there is an opportunity for a new head of department, we actively consider if that could be a woman.”

But overall, Werner is positive that women’s participation is slowly ticking upwards, and notes attitudes are changing. For one, when she first started her career, there were still “nudie girl pictures” in the unit trucks.

“That’s not the case anymore, thank goodness,” she says.

“The imbalance is getting better… particularly with Screen Australia supported productions, we’ve seen huge improvements. But that is not reflected in the whole of industry yet. And it’s certainly not reflected by all the makeup of the crew.”