Directors working in the streaming landscape and alongside showrunners must take a “humility pill” or “move to the exit”, according to Rachel Ward.

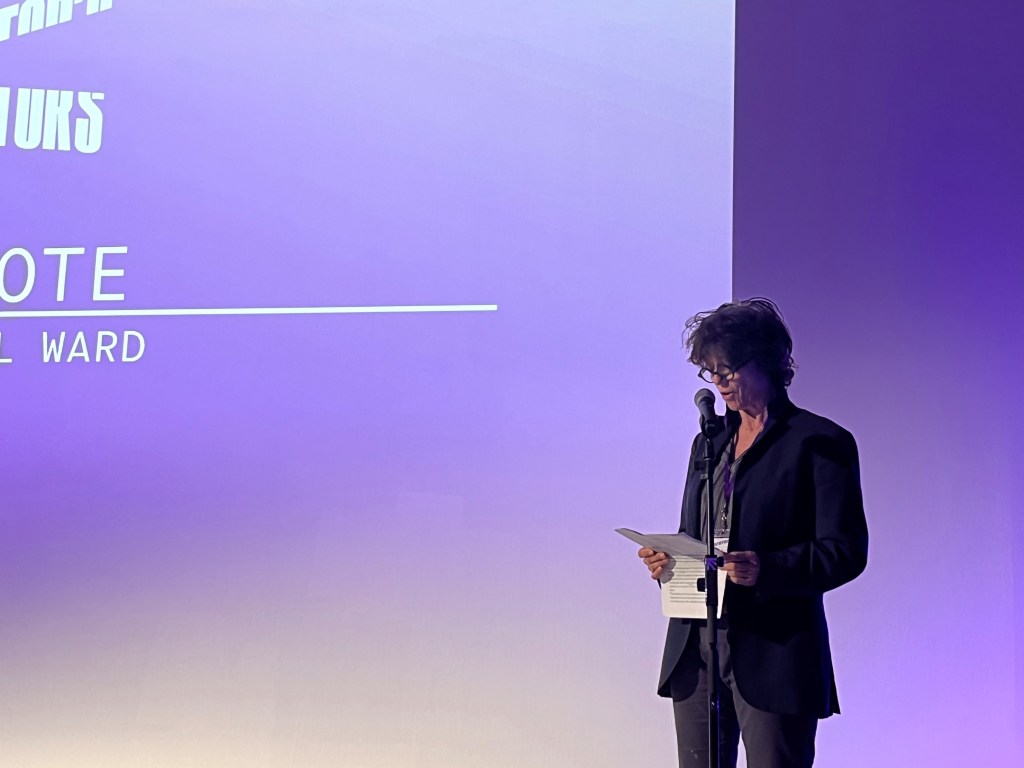

The director of films such as Beautiful Kate and Palm Beach opened the Australian Directors’ Guild conference, Director’s Cut, on Saturday in a keynote address.

In her speech, she referenced a controversial article she penned for the Nine papers in 2019, where she declared the director “dead” and wrote that today’s “Leans and Hitchcocks and Weirs” aren’t making film, but TV, where they have been “sadly neutered”.

“Producers and showrunners are the new brands, not the directors. They cast, they develop the scripts, they set the tone, they have final cut,” she wrote then.

Ward quipped on Saturday the piece did not win her many industry friends. However, she said she wrote it from her own experience.

Her own dose of “humility” came via a TV series where she “was not permitted to change one word of the script without prior consent”.

“I had to respond to eight pages of notes for a set-up episode from some invisible exec, deep in the streamer’s bowels. My editor was removed. Eventually I was too. And as small as our industry is here, I did not work again for many years,” she told the conference.

However, Ward said her most recent experience on a series “could not have been more fruitful, respectful and collaborative”.

“I am tempted to take back everything I said about our imminent death.

“But the truth is, the ground is shifting. And while we have enjoyed incredible autonomy and an unbridled voice in cinemas for decades, that platform, for most genres, is waning fast.

“Whether we like it or not, streaming – and with it our diminished voices – is the delivery service and the workplace for most directors of the future.

“It won’t be the same. We’ll have to conform to the streamer’s niche markets. We must do coverage execs may want, even if we don’t. We’ll get notes we have no option but to attend to. We won’t get the usual six to eight weeks to play in our edit; I have three days for a 35 minute episode in my latest.

“Of course there is no keeping good talent down. The best will rise. Their pilots will get picked up. Their set-up eps will rate the highest. They will be afforded the classiest fare; or they will develop, write and sell their own shows to streamers, and retain exec power. Either way, these director voices will increasingly be re-centred.”

Indeed, the role of the directors’ voice in a changing creative landscape – and their industrial rights – was among Director’s Cut’s key discussions.

In the “golden age of TV”, it’s not unusual to see six, eight or 10-episode series entirely shot by just one director, and to hear directors speak of how that creative opportunity presents to them like a “long film”.

But on that kind of project, whose voice is at the centre? Is it the director or the creative producer? What happens when you add a showrunner into the mix? Does a director get a say in major production decisions, like casting? Who gets final cut? Should a writer-director be able to be fired off their own project?

The role of the director continued in a panel session following Ward’s address, ‘Director at the Centre’. Moderated by ADG president Rowan Woods, it featured the Emmy-nominated Daina Reid, Bus Stop Films co-founder Genevieve Clay-Smith, Adrian Russell Wills and Partho Sen-Gupta.

Woods began the session by positing that throughout the history of screen storytelling, authorship has been shared in a “jostle-like manner” by directors, writers and producers.

“This movement, or this jostle at the centre is often rooted in a belief that a singularity of vision brings originality and coherence to screen storytelling.”

While collaborative practice was paramount, he added the director leads the interpretation of a text and the process of creating screen language – mise en scene – stating: “We must stand up for what that voice is worth to the screen project and to what it’s worth to the audience.”

There was an emphasis on a directors’ singularity of vision in the TV landscape like never before, Reid said.

However, if she was to have put on the ADG’s conference, she would have called it “Episode 8”, referring to some of her frustrations working under the showrunner model. She noted that often a showrunner’s attention is pulled in multiple directions, leading to script delays.

“I have been in the position where I’ve finished a few series. I never have that script. I wait and I wait and I wait and it doesn’t come.

“It all breaks apart at that point, because a director can’t direct, a producer can’t produce, and the actors can’t act if there’s no script. So if that showrunner has had their focus split so much they can’t deliver it to you, then where are we?”

In terms of how she sees the director’s role, Reid compared herself to a conductor, arguing the role is collaborative.

On that point, Clay-Smith agreed, noting her directorial style was that of “servant leadership”, as opposed to others serving her vision. That is, the creative vision is worked out as a team, with the director’s role then to get the best out of said team.

This idea of allowing others authorship in the creative process has informed her work with the disability community via Bus Stop Films. The concept of the auteur was not something that sat right with her.

“There is a way to have a creative vision and to lead with empathetic leadership; to be able listen to people, to give other people the space and to see them as valued members of the team, not just servants for the machine. That’s where inclusive filmmaking for me really came from; it was the idea of a shoulder-to-shoulder model, not a hierarchical model,” she said.

Contrastingly, Sen-Gupta argued the idea of the auteur needed to be reclaimed and revisited. They encouraged delegates to remember where the idea of the ‘auteur’ came from; a reaction against the studio industrial model in France in the ’50s where directors were seen as craftspeople – they believe we are at similar juncture now.

“I’d like to like to take that word back and own it. Yes, I do call myself an author-director because I am the author of the story and the film. As I go along, I work with different collaborators, all contributing to my vision in their own way. But they come and they go, and I continue to work on that project for a long time,” they said.

Wills added at times, strain on time and money on Australian productions – particularly in episodic TV – can mean a director is made to feel they are just there to “shoot a call sheet”.

“That’s when I start to feel my mental health declines, because I’m after the art; I’m after the performance, the storytelling… I think that’s getting further and further out of reach in this country.”

In another session, ‘Rights, Representation and Residuals’, RGM’s Jennifer Naughton and Frankel Lawyers’ Greg Duffy spoke to negotiating directors’ rights within the changing landscape.

Duffy said that over the last decade, he had increasingly observed directors getting siloed out of key decisions, though noted that was changing somewhat. Within that, he flagged concerns around showrunners ‘cutting behind’ directors across the US, Australia and the UK.

“You’ve got to be really clear about your vision, how you’re going to present it and what process, contractually, that means. So for instance… What period do you have to exclusively work with the editor to do the director’s cut? Then, who do you deliver to? Who do you take notes from? Do you get a chance to go back and interpret those notes and do another cut, and then who does it go to? That last jump is the bit that’s creating tension.”

Another growing trend was the early termination of directors. Naughton noted examples of clauses in contracts that would allow a director – shooting all episodes of a series – to be fired after the first episode if a platform didn’t like their approach.

Duffy cautioned termination provisions should be careful negotiated, particularly when the director was also the creator of the project. He noted that in feature film, there was a typically process before a director could be terminated: consultation, back and forth and then arbitration. He encouraged directors working in other mediums to also include an arbitration clause in their contracts, allowing a neutral party to resolve decisions quickly.

In terms of residuals, Naughton said that directors rarely see more than upfront fees on streaming projects. Both she and Duffy noted it is very hard for representatives, whether agent, manager or legal, to argue against the global might of streamers in contracting, with the argument often: “It’s been signed and used in 190 countries worldwide.”

In that sense, Duffy said there was a need for industrial action. “Writers, composers and producers around the world have been dealt into that particular pie for a long time. It’s only just started with directors in a small way.”

Further, Duffy noted that most countries around the world, except the US, have moral rights for directors, which involves the right to be credited and the right of integrity. He has started pushing this on contracts with global streamers as Australian directors are afforded these productions under the Copyright Act.

“We don’t want [directors] to be cut behind or pushed out of the of the consultation, collaboration process in the final delivery,” he said. “If the production company wants the director enough, there’s a discussion.”

Naughton said if a director waived the attribution of authorship in their moral rights, it was actually in conflict with their credit clause. “We keep raising this with the various legal teams that represent these companies, and it’s like bashing your head against a brick wall.

“These companies, most of them are coming out of the US. They have an understanding of working with the guilds there. Those guilds have such strong memberships, such strong powers. It very difficult for us to rely on that in this market without that industrial instrument in place. If we’re relying on the guild to step in and say, ‘Well, no, the director needs to be credited, and you can’t cut up their work’, that’s what the ADG should be doing.”

The ADG is finalising a TV director’s agreement with Screen Producers Australia.