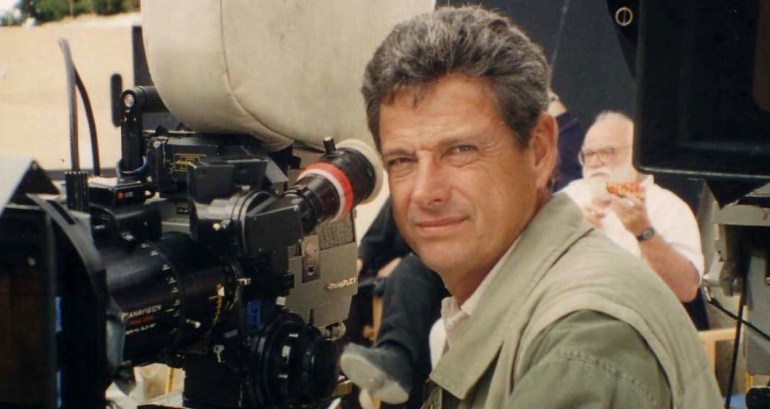

John Seale is one of Australia’s most internationally successful cinematographers, having been nominated for five Academy Awards, winning in 1997 for The English Patient. His work, along with the many other Australians who have made

in Hollywood, is being honoured in a currently being honoured in an exhibit from the National Film and Sound Archive. In this two part interview, Seale speaks to Jackie Keast about his career as he prepares for retirement, having wrapped on his final film, George Miller’s Three Thousand Years of Longing.

How did you get started or even interested in being in the industry? You began at the ABC in 1963, but at the time, there wasn’t really an Australian industry beyond that.

No, there wasn’t an industry, really. It was something that I fell into. I left school and I really didn’t know where I was going or which direction I should take. My parents couldn’t afford university and I didn’t pursue any further education. I was happy to go surfing. I kicked around at odd jobs in Sydney.

I love sailing, so I worked in a ship chandlery at Crows Nest for a while. I then went out jackarooing in central Queensland because I got the opportunity and I wanted to see what it was like on the other side of the mountains. I spent two years there and decided that the agricultural life was fairly hopeless, in that we’d had a five-year drought and we were right down to a minimum number of stock. Then the drought broke, and we lost another 30 per cent, nearly 40 per cent of that stock overnight from drowning because they got bogged and we couldn’t get them out. I thought, ‘This is ridiculous’. But I’d taken a lovely little 8mm camera with me to record my life and send it back to my parents. It was that little camera I kept looking at over two years and thinking, “I wonder if one day I could become a National Geographic cameraman or something – travel the world, film it for people”. I set that in my sights and here I am.

How did you get in at the ABC then?

Perseverance, which is something I’ve lectured to a lot of students who want to get into the game – that perseverance counts. I still feel it does. It took me a good, solid 18 months from the time I came back down from the bush. I met a friend of my family’s who was a cameraman at the ABC. That helped a little, because it got me an introduction into the ABC way of life, and I liked it. Then I pursued simply getting a job at the ABC and working the internal system, but I was also ringing the head cine cameraman every week for a year, saying “Would you have a job over there?” I think in the end, I got a job because he said, “Get that guy off my back, give him any sort of a job.” I ended up a driver film assistant and worked my way up from there. I fell in love with it, every minute of it, which I think helped me to stay in it for the long haul.

That was like your film school in a way. What did you learn about the cinematography through working at the ABC in those early years?

Well, the ABC back then had a lot of money, and the cine camera department wanted to spend it. They had 26 cameramen, and each one had his own little ArriFlex camera, plus a 70DR wind-up Bell and Howell. A lot of these guys were ex-World War II combat cameraman. A lot of them saw the Vietnam War and the Korean War with a camera. They were amazing because they were the old guys who’d come up through the very early stages of film work in Australia. Some through features, but most through news. You learnt so much about life; not only in how to operate a camera, but about people. When you went out to shoot a news story, they were teaching you about the philosophies of people and how to film them – how they could be nervous, how to put them at ease, what angles to use, how to talk to them, things like that.

We went from one department to the other. One day you could be doing news work, next week you could be going out to the outback to do rural coverage. All the different departments of the ABC offered a different variety of cinematic coverage. I was shuttled around so covered a big cross-section of cinematography, from documentary, news and then years later, they went into what they called drama and started shooting actors. That was another turning point.

How did you then cross over to into camera operating on feature film?

I loved the outback because I had been jackarooing out there for two years, and I did a lot of the documentaries out there with the ABC. Then they started this drama department, and one of the first things we did was in the outback, called Wandjina!, which is Dreamtime. It had the beautiful Jacki Weaver in it. I think she was 16 or 17. All of a sudden there I was in the outback, and instead of cows and sheep to film, we had actors in front of the camera performing a dramatic scene of some kind. I found that

so exciting, that combination. I knew from then on that I would pursue cinematography in the drama world.

You came up during The New Wave, The Renaissance. Some of your early camera operating work was done with Peter Weir. What was that time like?

That was a very exciting time in Australia. We went for a long time without any cinema movies; it was all TV, documentaries or news. But suddenly there was a renaissance, and I was lucky to be on the forefront of the wave. You could sense everybody getting very excited about it, not only crew who were now working on feature films, but also producers, directors, writers and the money people. Those early films of Peter Weir’s and Gillian Armstrong’s – there were actually about five directors who actually really got it going – were some of the most lovely, authentic Australian dramas. They started to find a world audience. I was able to progress in the early days as a focus puller, then I became a camera operator. I loved camera operating so much, I stayed there while all my friends went past me and became directors of photography. It allowed me to meet people like Peter Weir and a lot of other directors who went on to become international.

It was a lovely time. I think we all starved a bit. I know I did. We were sitting on the front step of our mortgage-ridden house with two children, a dog and a station wagon, with our head in our hands, saying, “What are we going to do now? We’ve got no money and there’s no jobs”. It was hard times in those early days. It made the excitement of getting a job even more profound. You wanted to make that the best movie in the world. Maybe that’s little bit of the underlying reason for the successes; a lot of those early films we all rallied to make as best as we could.

So how did you cross over from camera operating to being a DOP? Afterwards you also went back and did camera operating on films like Gallipoli too.

As I said, I loved camera operating, I just found it one of the most exciting jobs you could ever do. You’re working very closely with actors. In those early days when the director didn’t have a monitor, it meant that the reliance on the camera operator was enormous. You had to analyse what you had recorded as to whether or not that was technically viable for the shot to then be put in the can, printed it up and used in the film. That responsibility was pretty amazing, and it’s part of why I loved it. But I also loved watching the actors strut their stuff. They’re the most interesting people in the world. They have to go from being ‘me’ to being ‘him or her’ – a different person – and that creates a whole challenge within them. And we have to try and help them along that journey.

But I went along for an interview with Maurice Murphy, and I naturally thought I was being interviewed for camera operating. I said, “Well, who’s lighting this thing?” They were dead silent. Maurice and the first assistant, Mark Egerton, looked at me and Maurice said: ‘We were hoping that for an extra cup of tea with sugar a day, you would light it as well’. It was very low budget. I had to take a deep breath on that one.

I had done one little film for Brian Trenchard-Smith before then called Deathcheaters. I was terrified of it and quietly went back to operating. Then this one came along for a couple of tea. I did it and I liked it. I thought, “This is quite interesting.” So I started to light and operate, which is a big work burden, but it’s one that’s very satisfying. I fell into that for the rest of my life, basically.

Check into tomorrow to read the second part of this interview with John Seale, in which he discusses his transition to working in Hollywood and working on his last film, Three Thousand Years of Longing.

This article was originally published in IF Magazine Feb-March #204. Subscribe to the magazine here.