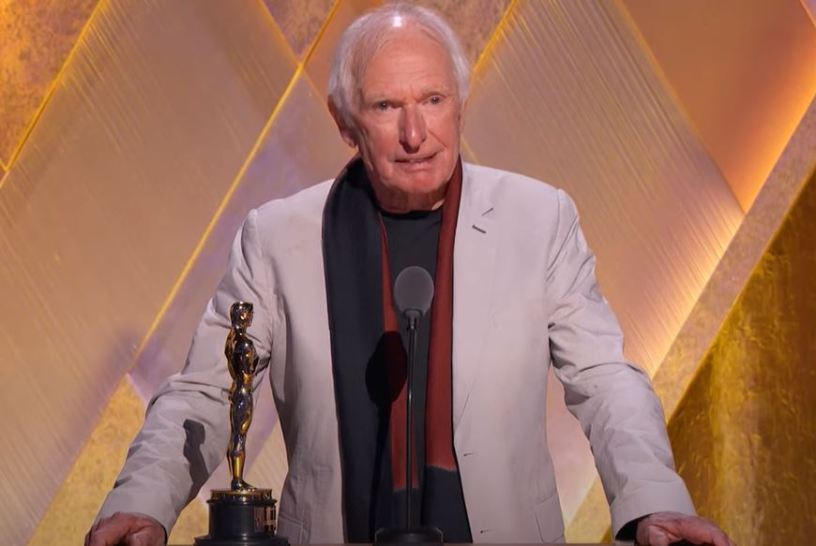

Peter Weir reflected on the two halves of his career – one in Australia, one in Hollywood – as he collected his honorary Oscar at the Governor’s Awards in Los Angeles.

The director was one of was of four honorees of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) on Saturday evening (LA time), alongside Euzhan Palcy, Dianne Warren, and Michael J. Fox, who received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

Over his career, Weir has been nominated for six Oscars, with directing nominations for Witness (1986), Dead Poets Society (1990), The Truman Show (1999) and Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2004), for which he also also received a Best Picture nomination. In addition, he earned a writing nomination for Green Card in 1990.

One of Australia’s most celebrated directors and a pivotal figure in the Australian New Wave of the ’70s, Weir’s credits also encompass Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Last Wave, Gallipoli, The Cars That Ate Paris, The Way Back, Fearless, The Mosquito Coast and The Year of Living Dangerously.

Weir was presented the award by Jeff Bridges, who worked with the director in Fearless. In his introduction, the actor noted the tone Weir created on sets, his quest for truth in performance and how he pushed him to rise above creative bumps in the road.

He jokingly recalled the first piece of direction Weir gave him: “You looked at me and you said ‘Jeff, we’re going on a wild adventure now, and I need you man. I need everything you got. You’re going to be my co-pilot on this. We’re going to fly this plane together’.

“I thought, ‘What a wonderful invitation.’ And then I thought, ‘Gee, our movie’s about a plane crash. I’m not going to be helping you to drive this thing into the ground man’.

“I’m glad it didn’t work out that way; I had a wonderful experience.”

Accepting his award, Weir reflected on the early days in his filmmaking career, which coincided with the revival of Australian cinema.

“I was fortunate to be around when our moribund film industry came to life again in the late ’60s, early ’70s. We knew nothing, but we were determined. What we did know was about our love for movies.

“We had no older generation that you could sit at the feet of and ask them what it’s like and what do you do, but we did have film festivals and we saw the best of world cinema,” he said.

“We were flying there with very little experience, but what a way to learn. There were no film schools, there was no one to tell you you were wrong. There was no one to tell you ‘What a dumb idea’; it was just ‘Let’s go, let’s do it.”

In the ’80s, Weir said he began to feel restless. “I felt like I needed new inspiration, new energy, new landscapes, different ideas. I was ready for change. I was ready for Hollywood.”

His agent introduced him to Jeff Katzenberg, which lead to Witness – a film Weir would shoot alongside collaborator and fellow Aussie, cinematographer John Seale. It was nominated for eight Oscars, winning two.

“So I got off to a good start and had a wonderful 20 years of making studio pictures. I love the history of it all… I was delighted to be here [in the US]. You’ve got a such a great industry. Such a short history – I was thinking talking pictures aren’t 100 years old. I know we’re going through tremendous changes. You’ve done so much, you’ve produced such wonderful films and such wonderful people, and you’re so welcoming to foreigners like me.”

Weir also paid tribute to his “cast and crew”, though argued it should just be one word as “whether you’re in front of the camera or behind, we’re all in the same team.”

Weir compared filmmaking to the journeys of explorers like Shackleton, with a director pulling together a crew “knowing they’re going to get be under stress at certain times; not just physical, but emotional stress.”

“Putting your crew together, one, you want talent. You want people who know the job. Then also you want people who can handle a tough and tight corner – a difficult situation. That will come up; you want to be able to trust them.”

Weir said he was always interested, going back to his work in Australia, in who his heads of department were hiring and bringing everyone in to the same vision.

“I think a group of people doing something does create a kind of energy; it goes around. I love that and my crew always knew that it was not about my ego or their ego; it was about the film’s ego. The film has an ego and we’re there to serve it the best we can.”