When AI-powered chatbot ChatGPT was launched in November last year, its ability to write loglines, treatments and even basic scripts shocked the industry – reigniting debate about the merger of these technologies with human creativity.

Steven Spielberg said the idea of machines writing movies, books and music terrified him. Guillermo del Toro and Hayao Miyazaki went so far as to say AI-created art was “an insult to life itself”. Writers feared the technology could see them made redundant.

However, what if creatives were put at the helm of this sort of technology? What if it could expand their ideas, or help them develop complex story worlds and nonlinear narratives? The Australian-based Othelia is an intelligent software company aims to do just that: Put creatives in the driver’s seat and give them tools to enhance the magic of human storytelling.

The company was co-founded by Kate Armstrong-Smith and Joe Couch in 2019. Each have a background in the arts and screen industry, and have long been interested in how systems theory, technology and storytelling could merge. Informing their work is a team of creative brains; writers, directors, producers, artists, academics and data strategists.

Underscoring Othelia’s developing work is a passion for story, understanding of the importance of narrative structure, and an abiding respect for the creative process. Early backers include Deanne Weir and Olivia Humphrey’s Storyd and the LA-based female-focused fund Aliavia, and it has also received funding through the Federal Government.

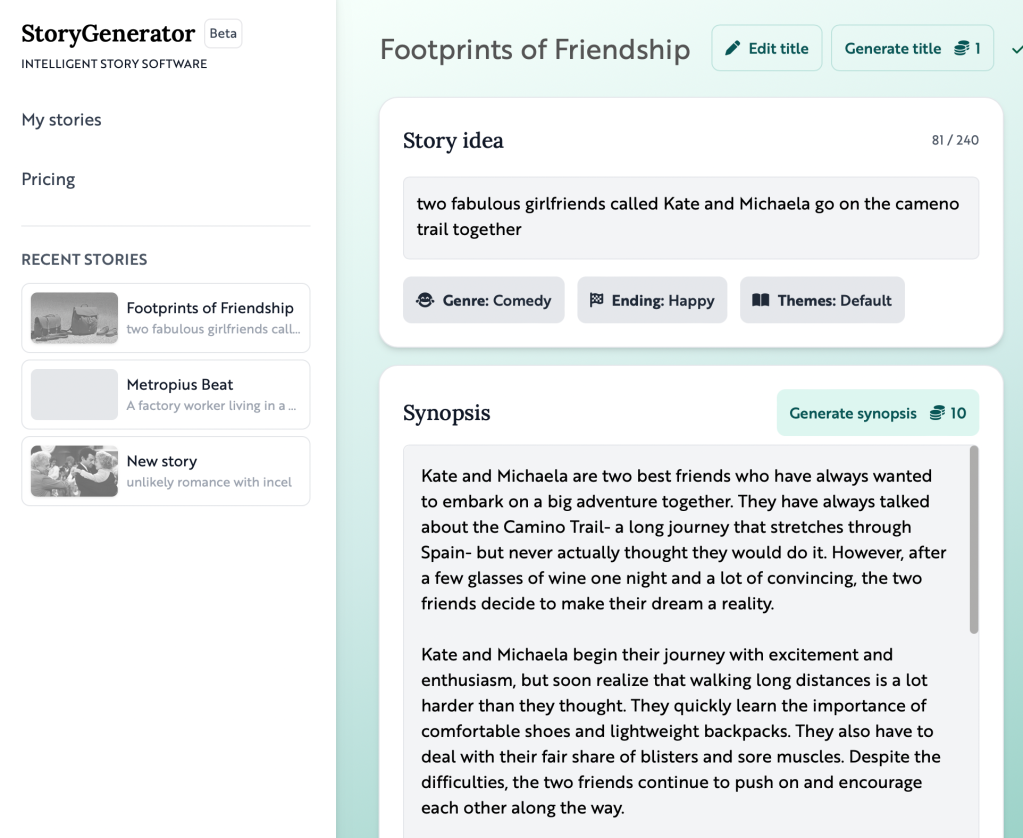

After ChatGPT was launched, Othelia released its Story Generator app in response. It was a tool specifically designed to see creatives turn an idea into a first draft in seconds. It was also an experiment: To get creatives to explore and debate the use of intelligent tools in their practice. In response to feedback (see box below), Othelia has recently updated Story Generator so that it is now a co-writing companion tool, enabling creatives to experiment with genre, themes, characters and plotlines.

“We’ve now seen and heard people say that tools like ours have real potential to take care of the heavy lifting or story structuring, and allow writers to focus on the more creative aspects of their work,” CEO Armstrong-Smith says.

However, Story Generator is just the start for Othelia. The company is also building a suite of tools that aim to bring development into a new era.

“We’ve been able to marry our backgrounds in story and narrative modelling with new technologies to create something truly useful. The full Othelia suite will be like nothing that exists right now. It will work for storytellers using traditional formats as well as new environments like XR/VR. I can’t wait to share it,” Armstrong-Smith says.

Building story worlds

Othelia’s company approach takes inspiration from feminist sci-fi writer Ursula Le Grin’s essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, which calls for an alternative to the monomyth and embrace of rich, textured and layered stories that represent the complex human experience.

To that end, Othelia is building software that aims to allow writers to experiment with new and unconventional ways to see and map story in real-time – non-linear narratives, multiple perspectives, timelines and storylines. Writers and producers report to them that often they contain the rich details and subtexts of their story worlds in their heads – that scripting and paper are outdated story devices in the era of gaming engines.

Armstrong-Smith and Couch first observed systems theory could be applied to storytelling back in 2016, allowing for the mapping of complex story worlds.

Their initial break came via Amazon Studios on The Lord of Rings: Rings of Power, for whom they were engaged to organise story material from the Tolkien books. The team continued to refine their story system with further Hollywood and Australian companies, noting it gave writers and producers more options and narrative opportunities.

However, Armstrong-Smith and Couch continued to find writers were nervous about ‘efficiencies’. Instead, they wanted tools to enhance their creative experience. After meeting with visual effects maestro Kim Libreri, who spearheaded Unreal Engine uptake in Hollywood, they realised by converting their story system to software, they could create an engine that managed real-time story modelling.

They pivoted to researching and developing writing tools and other defining technologies to enhance creativity – and thus, Othelia was born.

Nicholas Lathouris, co-writer of Mad Max: Fury Road and Furiosa, is among the creatives who has worked with Othelia to develop and refine its tools.

Lathouris has long been interested ways to deconstruct story structure in film and television – ways to tell stories beyond the hero’s journey. His projects include non-linear stories with multiple storylines and characters set within the one overarching universe.

“Othelia and AI seemed to have the potential to handle these large quantities of material and organise them into a meaningful set of structures with aesthetic appeal and simple rules capable of multiple iterations,” he says.

“I’ve been developing a non-linear project for many years – over 20 – accumulating material branching out from a central idea into many storylines with many characters that need to be drawn together. There are many threads that need to be woven into a singular aesthetic work. It’s so big I could categorically say that no human being can contain it or make sense of it.

“If there was something of worth in all that mess and chaos then perhaps only Othelia stands a chance of finding it and, perhaps even organising it into something revelatory.”

Embracing the human

Rather than an existential threat, Lathouris sees AI and Othelia’s tools as a “workstation” replacing “three screens, multiple open windows and programs, as well as my physical library.” To write with AI is to have a conversation – one that gives access to “ideas and thoughts outside of our immediate field of vision.” It is then up to the writer to iterate and interpret the material.

“As a human, I’m still tasked with making the decisions; I’m still tasked with the evocation of emotion and meaning for the receiver. It’s a tool. Perhaps it could be more than that, but we’re not quite there yet,” he says.

Indeed, he believes human oversight and care will always need to be applied.

“Collaborating with writing tools helps me refine my story ideas, which is helpful. But the health of the story, the ethics of care in storytelling – that’s always going to be in the control of the person using technology. And consequently, and most importantly, that’s where the art is. It’s a verb, not a noun. It’s the how, not the what. And certainly not the who.

“And I do think that given the potential risks, we’re always going to need humans to interact with it to make sure we design tools and technologies that service us beneficially; bring us together, connect us.”

Ultimately, Lathouris acknowledges the fear many have, but counters that if AI can produce a text that has meaning for an audience, that would seem to justify its existence.

“It’s the same principle or aspiration I have as a creative. If we eliminate ‘ego’ from that principle, what difference does it make whether I do it or it comes out of machine, as long as the outcome has a benefit to its audience?”

ChatGPT and the rise of intelligent story software

Othelia initially created Story Generator as an online experiment – a conversation firestarter to draw attention to the power of ChatGPT-style tools. It has since been evolved into a writing companion.

This is the feedback it received to its initial version, which provides food for thought as the industry engages with these new technologies:

Writers and producers are worried about the safety of their stories.

When language engines are used, the engine stores and repurposes your content. It is highly possible, and examples of this are appearing, that stories and information inputted are being repurposed and provided to other users without any clear definition of copyright or tracking of ideas. Just recently in March OpenAI changed its policy to state that no data submitted by the customer would be used to train its data models. Writers and producers want the copyright and chain of title to be clear if they use generative engines as aids. Having guidelines from authorities like the Writers Guild of America is essential. Creating clear guidelines around using generative engines, what is deemed plagiarism, and what has been deemed a work that can be titled (and a chain of titles initiated) will determine how intelligent software will be engaged.

Story creators want tools that enhance their creativity rather than generate it for them.

Co-writing and co-creation are the most popular engagement with these tools. Othelia’s research shows that getting the engine to construct a draft from your prompts and then the ability to edit and refine is creators’ preferred way of engagement.

ChatGPT doesn’t always enhance creative paces – Othelia found that creatives need ‘lean-back writing tools, not lean-in’.

The director’s unit or the writer’s room want to be focused on brainstorming and reflecting, not on the technology program they are using. In this way, technology must enhance environments and creative process by summarising and informing when they need support. The question of creative privilege and software tools allowing people with finite resources and time to create high-quality story worlds is a current debate. Some creatives are afraid that the engines are soulless and

not creatively valid – there have been some heated publicised opinions from cultural veterans such as Steven Spielberg, Guillermo Del Toro, Nick Cave and Noam Chomsky, who detest the advent of AI generative text. On the other hand, many are excited about being able to edit and get their writer’s block cleared. Time-poor creatives are using productive AI tools to initiate first drafts that they can ‘imbue’ with creative meaning, and Othelia sees uptake this way as being popular.