In the era of “content” and streaming, Clara Law feels it’s harder than ever for cinema to be considered firstly as an art form, or a form of cultural preservation.

Instead, she sees projects marked by creative compromise.

“There’s a lot of disappointment watching films nowadays, because there’s a lot of compromises out there, even with soft money,” the Macau-born, Hong Kong-raised and Melbourne-based filmmaker tells IF.

“Even in Europe, they have to go to different countries to get different soft money to make it happen.

“You move a little bit for each producer. You lose the original and you have to be very aware of that; you just cannot move too far from your own vision until it becomes nothing, it becomes something just bland and generic.

“And simplistic too… We divide things into black and white, and then we end up with something that is uninteresting. [To be] uninteresting is the worst thing that we can do as artists, I think.

“Why do something that someone has done before? Why don’t you do something fresh and original?”

The idea of compromise has been on Law’s mind as she helped ACMI and the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) put together a retrospective of her work, which runs this month in Melbourne and in March in Canberra.

Along with her co-writer and closest creative collaborator, husband Eddie L.C. Fong, she selected all five of the films to feature.

They include the recently NFSA-restored Floating Life; a 1996 landmark title for Asian-Australian cinema; Autumn Moon, winner of the Golden Leopard at Locarno in 1992; 2000 Rose-Byrne starrer The Goddess of 1967; Law’s 1985 graduate film They Say the Moon is Fuller Here, and her most recent work, Drifting Petals, which won Best Director at Taipei’s Golden Horse Awards in 2021.

Considering her oeuvre, Law feels these projects are the ones that best speak to an Australian audience, but also represent those where she had to compromise the least.

“There’s a big difference when you have to compromise. Of course, compromise is up to a certain point. I always have a bottom line. I don’t cross that line; I would not ever in my creative life do that and I don’t think I have.

“But still, when you have total liberty, it is a different thing.”

They Say the Moon Is Fuller Here, which will make its Australian premiere through the retrospective, was written and directed by Law while studying at the National Film School in England; not content to make a short like other students, she pushed to make a feature.

The drama follows two lovers grappling with the incongruity between cultures; Lau Ling (played by Law) is an art student in the UK originally from Hong Kong who meets Han Wah, a Chinese student traumatised by the Cultural Revolution.

On a student film, Law notes you have “total freedom”, limited only by your own experience and a lack of money.

By comparison, on ’92’s Autumn Moon – about a Hong Kong high school girl who befriends a 20-something Japanese man – Law felt for the first time she had money upfront to execute on her vision. The 108-minute feature was financed via a 60-minute home distribution deal for Japan; it was a small budget, but there was no commercial pressure.

“We just used that money and did it a little bit like a student film. It was one month, no rest. The crew all upgraded, the gaffer to be something else, the art director to be a production designer. It became their first experience, so everyone put their best into it,” she says.

“I felt totally liberated doing it the way I liked. Except for the budget, but you just have to make do with what you have.”

Floating Life, produced by Felix Media, then marked Law and Fong’s first film made in Australia after migrating here in 1995.

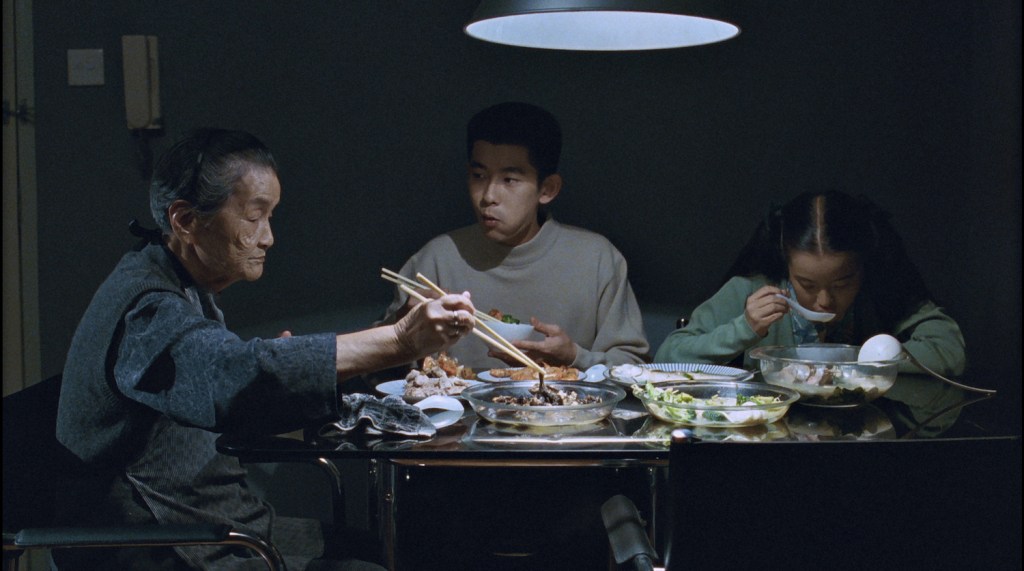

It follows a Chinese family from Hong Kong who migrate to the Australian suburbs to join their adult daughter, who has already been living here for seven years. At the same time, their eldest daughter is in Germany and their eldest son remains in Hong Kong, with the film weaving between the different ways the family members cope with isolation and alienation.

Floating Life was the first Australian film to ever be submitted for the Foreign Language Oscar, and has an enduring legacy as one of the first examples of Asian-Australian cinema, with creatives such as director Corrie Chen and writer Benjamin Law speaking of its influence on them.

“When you first arrive at a place, your senses are very acute and you are very attuned. You’re curious,” Law says.

“It was our first time stepping foot on the earth of Australia. I have all these memories of my arrival; the smell, the colour, the look, the visual. Everything was so strange, but fresh and different from Hong Kong – crowded, polluted and colourful and all of that. You wanted to capture, instil that and reflect it, so that it’s like in this time capsule where you could look back… It’s not autobiographical, but it has your own emotion; the feeling of being an immigrant, the feeling of leaving a place, putting that behind you.”

Also set in Australia is Goddess of 1967. It follows J.M., an avid Japanese car collector (Rikiya Kurokawa) who travels to rural Australia in response to an advertisement for his dream vehicle – a Citroën DS, nicknamed “The Goddess”. J.M. gets more than he bargained for when a blind girl, B.G. (Byrne), answers the door and hitches a ride with him to the outback opal mining town where she grew up.

“Goddess, it was an experiment. With Floating Life up to the Goddess we were in the golden period of funding,” Law says.

“There was a lot more liberty, a lot more freedom, a lot more money – not like now. We didn’t need to conform. We could think of what we wanted to do, experiment with our structure, with the way we wanted to tell a story, with the narrative.”

It’s perhaps Law’s most recent film, Drifting Petals, that best encapsulates her idea of “total liberation” in terms of uncompromised filmmaking.

Described as ‘alternate cinema’, the story weaves between a filmmaker and a piano student – who first meet in Australia – as they try to make sense of a past imbued with mystery in Macau and an uncertain future in Hong Kong.

Made over five years at a micro-budget, Law and Fong took on most behind-the-scenes roles.

“It was totally DIY. We set up a home post-production studio where we did our own editing, our own sound, our own grading, did the DCP,” Law says.

“You could work in the middle of the night; no one was going to kick you out of the studio. Whatever you liked, you did it and then if we felt we’d come to a point where we had to stop, think a little bit more, we could stop. There was no commercial pressure or any kind of industry pressure.”

As a child, Law recalls when she used to build houses with blocks, her mother would note how she always gave each house a bridge. That still drives her today; a desire to build bridges between cultures in her work, but with nuance and detail, and emotion conveyed in visual language rather than exposition.

Law hopes her and Fong’s next project will be The Little QiPao Shop, which they are developing with Film Art Media’s Sue Maslin and Charlotte Seymour. She describes it as advancing from Floating Life in that the plot follows second generation Asian-Australians.

“It is about how to find a balance, to live together… To be able to live in harmony and peace within the family itself and also with your own rich culture,” Law says.

“We talk about multiculturalism; I came here with that very optimistic view that Australia is the best place that I have been in the places I have travelled to. I’d been in the UK for three years, I’d been I worked in New York for a little bit and this was the place.

“But multiculturalism is not just about dim sim. It’s not just about Chinese food or Indian food or curry. It’s deeper than that… There’s uniqueness in each culture. I’m sure as a country that embodies so, so many different ethnicities, we could learn from each other; be richer that way.

“So The Little QiPao Shop is with that vision in mind.”

Floating Life opens Focus on Clara Law at ACMI tonight, with films running until February 26. The NFSA season runs March 3-4.