In terms of efforts to bolster on-screen diversity, Screen Australia CEO Graeme Mason says the industry “can get a tick” but “we don’t get gold star yet”.

Screen Australia released today the follow up to its landmark 2016 report Seeing Ourselves: Diversity, equity and inclusion in Australian TV drama.

While marked improvements have been made, a significant number of Australian communities remain under-represented on the small screen compared to the population, and disability representation is still critically low.

The 140-page report, Seeing Ourselves 2, examines 3,072 main characters in 361 Australia TV dramas, including children’s and comedy, commissioned and first released between 2016 and 2021 on FTA or subscription TV, streaming services or online.

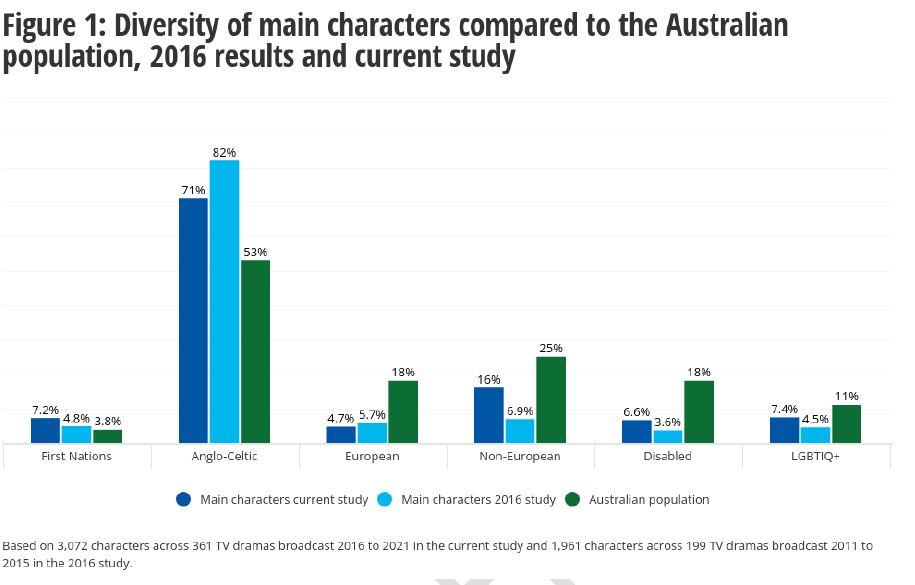

Compared to 2016, today’s report suggests there are now substantially more main characters on Australian TV who are First Nations, non-European, disabled or LGBTIQ+. However, with the exception of First Nations people, all remain under-represented, particularly disabled people.

Reflecting on the results, Mason tells IF that he would like the pace of change quicken, especially in disability.

“We as a cultural agency particularly recognise that Australian screen stories need to reflect Australia as she is,” he says.

“I’m happy that everything’s moving in the right direction. I’d really like to see the speed of it increase.”

Mason notes while Screen Australia and other organisations, including broadcasters and state screen agencies, have run many successful diversity initiatives, attachments and placements in recent years, he flags this report shows a need for more targeted and co-ordinated collective effort.

“One of the things I’m really excited by this report is it gives us data. It can focus us all… We did Digital Originals, for example, with SBS for under-represented creatives and we did DisRupted with ABC for disabled practitioners. We’ve done lots of placements. But I think what this is going to give us the drive to do is much better coordination.”

When it comes to cultural diversity, Seeing Ourselves 2 shows characters of Anglo-Celtic background (such as English, Irish, Scottish or Welsh ancestry) continue to be vastly over-represented on Australian TV screens, making up 71 per cent of main characters compared to 53 per cent of the Australian population. However, this in an improvement; in 2016, 82 per cent of main characters were found to be of Anglo-Celtic background.

One in four TV dramas feature entirely Anglo-Celtic main characters, though this is down from one in three in the previous study.

First Nations people now make up 7.2 per cent of main characters, compared to 4.8 per cent in 2016 and a population benchmark of 3.8 per cent.

The report suggests Australia leads the way among US, Canadian and New Zealand counterparts in this regard, something that is testament to more than 30 years of collective effort from organisations Screen Australia, ABC, NITV and AFTRS. As highlighted in the first Seeing Ourselves report, in 1992 there were no First Nations actors on screen, and in 1999 there were just two: Aaron Pedersen and Heath Bergerson.

However, First Nations characters continue to be concentrated in a few titles, such as Cleverman, Black Comedy, Wentworth and Mystery Road; three quarters of Australian dramas have no First Nations main characters. First Nations characters were also more likely to appear as sketch comedy characters, supernatural characters, students or criminals. Among First Nations characters there are also lower rates of LGBTIQ+ and disability representation.

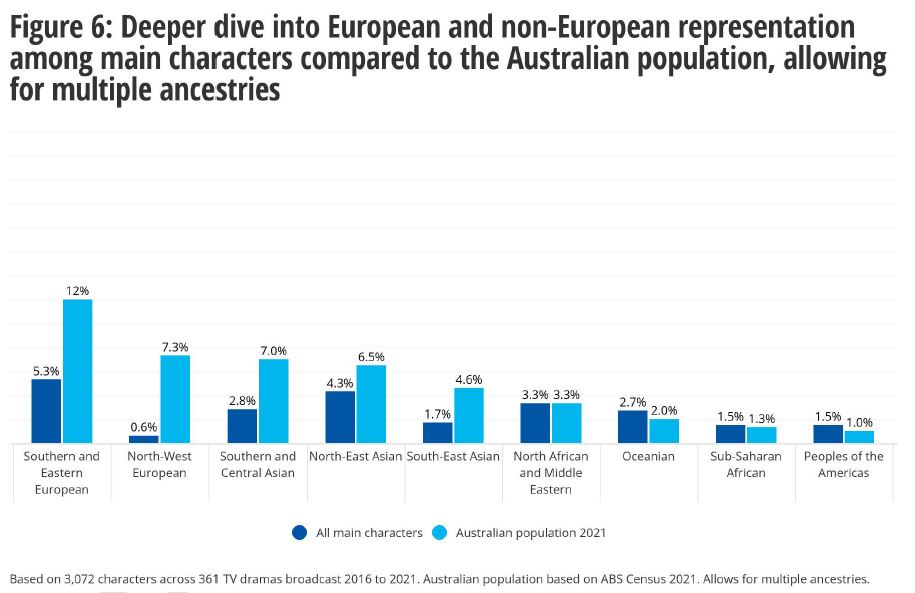

The share of non-European main characters on Australian TV, such as those with Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese or Middle Eastern ancestry, has more than doubled to 16 per cent compared to 6.9 per cent in 2016. However, this still trails the population benchmark of 25 per cent. Broken down further, Southern and Central Asian and South-East Asian groups are particularly under-represented compared to the population (see below graph). A slim majority of Australian TV drama featured non-European main characters.

Notably, representation for people of European background (for example, characters with German, Dutch, Italian or Greek ancestry) has decreased since 2016, dropping to 4.7 per cent compared to 5.7 per cent.

People of European background make up 18 per cent of the Australian population. While the report notes its figures suggest under-representation, it it also may reflect “many Australians with European ancestry now have anglicised names, making them harder to identify – ancestry is not always apparent either on screen or in daily life.”

“Our on‑screen stories feature relatively few main characters who have specific story elements (such as name, language and family members) that represent the diverse communities within this group,” the report states.

The report also considers the backgrounds of actors, and notes there are higher levels of European and non-European representation among them when compared to the characters they play. The researchers extrapolate that this is therefore an opportunity for more “colour-conscious casting, which involves intentional consideration of an actor’s ethnicity and how it enriches a character’s identity and the story.”

The representation of disabled people on TV has nearly doubled, up to 6.6 per cent of main characters from 3.6 per cent in 2016. However, this increase is from a low base given nearly one in five Australians have a disability (18 per cent). Nearly three quarters of all programs studied did not feature any disabled main characters.

When disability was portrayed, it was most commonly a psychosocial disability, such as barriers related to memory conditions or mental illness, or a physical disability, such as chronic pain or wheelchair use. Portrayals of other experiences, such as sensory or intellectual disability, were less common.

LGBTIQ+ people make up 7.4 per cent of main characters, up from 4.5 per cent in 2016. The population benchmark is 11 per cent. Seven in 10 titles feature no LGBTIQ+ characters, and of those that do, half feature just one. More than one in two LGBTIQ+ characters are women, and there are higher rates of LGBTIQ+ representation among characters who are non-European or have a disability. Nearly all trans or gender diverse characters were played by actors who publicly identified as such.

In terms of age, most Australian TV focuses on younger adults, with 62 per cent of main characters 18-44 years old and living in capital cities. People under 12 are highly under-represented (2.2 per cent compared to population benchmark of 15 per cent), as are characters 60 and over (7 per cent compared to 23 per cent of the population).

Main characters in TV drama were also found to have higher occupational status than the Australian population, suggesting a bias to socioeconomic advantage. First Nations, non-European and disabled characters were also less likely to represented in higher skill level occupations.

Overall, children’s drama has a higher level of cultural diversity than general drama in terms of First Nations (9.1 per cent of main characters) and non-European representation (22 per cent). However levels of disability (3.8 per cent) and LGBTIQ+ representation (3.1 per cent) are lower.

Comedy titles feature higher rates of First Nations and non-European representation, which the report suggests may reflect a greater appetite for risk in commissioning. However, like in children’s, disability and LGBTIQ+ representation is lower.

Seeing Ourselves 2 also includes qualitative research, based on interviews with 28 practitioners and 35 representatives from a variety of organisations, including diversity, equity, inclusion and human rights organisations; guilds/industry associations; education and training and broadcasters/streamers.

It found significant barriers to improving on-screen representation and diversity and inclusion off screen in production teams, writers’ room and key decision-making and commissioning roles, but notes a push within industry for lived experience and genuine collaboration in telling authentic stories, diverse representation at all career stages, and for improving the industry’s cultural safety and accessibility.

Mason says a diversity of characters on screen is not just a cultural or moral imperative, it’s also more creatively interesting and makes commercial sense in that it speaks to the widest audience possible and to people’s desire to see themselves on screen.

“The goal for the sector is to have our screens representing what it’s like when you walk down the street in Australia.”

While the report only includes data up to 2021, Mason believes change continues in projects released within the last year such as Heartbreak High, Latecomers, Mystery Road: Origin, and Bad Behaviour, and upcoming projects like the second season of RFDS and fourth season of Five Bedrooms.

“It feels like we’re continuing the momentum. We have to keep our eye on it like we’ve done with First Nations; we’ve kept our eye on it for 30 years. We have to do the same thing here and it will work therefore creatively, culturally and commercially.”