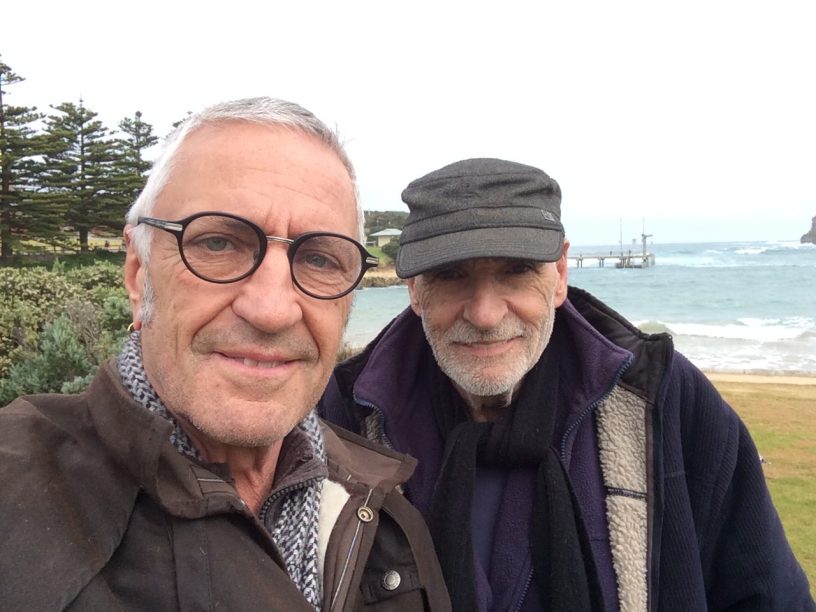

AWGIE-winning screenwriter, independent filmmaker, musician and painter Luis Bayonas died peacefully in the early hours of Thursday, July 6 with his son Daniel by his side. Luis was 90 years old. Actor John Waters has penned this tribute to an unsung legend of Australian screen culture.

Luis Bayonas was my closest friend. We were never really similar, but there was a ‘place’ of some kind in the ether where we were totally compatible.

I met Luis in 1973-4 (Fuck! 50 years ago!). His wife Lyn was working as a script editor for Oscar Whitbread on the new ABC TV Melbourne series Rush which I little realised at the time was destined to be a huge hit for all of us.

A couple of years earlier Lyn had been in the rather exotic job of PA to Orson Welles in Spain, where the great actor/director lived and worked in a kind of exile. She told me that her closest friend over there was an English woman, recently separated from a Spanish man with whom she had had two daughters. Lyn had met the man, whose name was José-Luis de las Bayonas (or just plain Luis) and thought him staggeringly handsome. Her friend said: “He’s a fucking nightmare. Take him, he’s all yours.” And Lyn did.

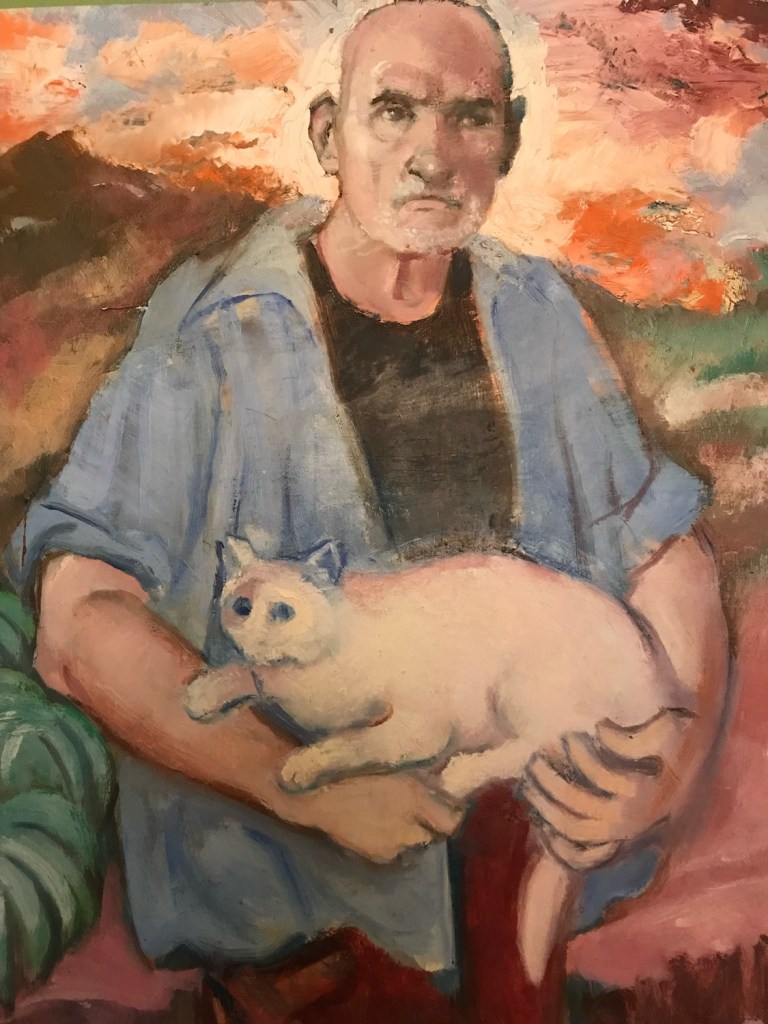

It turned out that apart from his matinee idol looks, Luis was a gifted painter of works that were hung in many galleries, a classical pianist trained at the Conservatorium in Madrid, and a second unit director, first AD, set decorator and a script writer on international movies shot in Spain (he even acted alongside Dustin Hoffman in the star’s first movie, Madigan’s Millions!). I never found out if Luis was also a nuclear physicist, but no doubt one day I will.

After finishing her job with Welles, Lyn Bayonas (she took his name but never married him) arrived back in her hometown of Melbourne with a large multi-talented and heavily-accented Spanish man in tow. Through her connections at Crawford Productions and a script Luis had written, Lyn astonishingly secured her ‘husband’ a job as a staff writer on the cop show Homicide.

Luis was extremely fluent in English, but many times over the years I have had to act as his interpreter because of the way he spoke it. I speak some Spanish and we used to chat in his language to avoid other people knowing what we were saying, but I had to translate his ‘English’ into English that others could understand. Everything was in a fast, guttural drawl, and every other word was ‘fuck’, ‘fucking’ ‘whatthefuck’ or ‘fucking shit’.

In his time at Crawford Productions, Luis rapidly became a legend. With no knowledge at all of Australia, he reeled off episode after episode of ground-breaking television. One Homicide ep I remember in particular was a surreal story that turned out to be an entire ‘dream sequence’. Nobody, including Tony Morphett, David Boutland, Cliff Green, Sonia Borg and Peter Schreck had ever written anything like it. It was outside the Homicide brief, and yet, as with so many things in Luis’ life, what he did was somehow magically accepted.

On top of that, Luis called the shots on the punch-drunk Crawford’s execs. He refused to go into the Crawford’s HQ in Abbotsford and clock in to sit at a desk and write, because he was not “a fucking moron public fucking servant”, and was duly allowed to write from home.

As the series Rush was being shot, and forever afterward, Luis and I hung out at every opportunity. Our work eventually took us to different places, but we – and the brilliant Lyn – would always contrive to hook up. One such time was the movie Angel Gear, which turned out to be an unmade gem fraught with disaster.

I was to play a loner who hitched a ride with a truckie (to be played by the late John Ewart) from a ‘city’ somewhere in an unnamed country across a vast desert (the Nullarbor Plain). Part of the journey involved putting the truck on the ‘piggyback train’ at Port Augusta, where the horrible abuse by men in shorts and singlets of the train’s resident sex worker, a young Indigenous girl, was depicted quite graphically, to the horror of the naive hitchhiker. The script ended with the two utterly different men alone, broken down and stranded in a desert, eating the truck’s cargo, which was ten thousand packets of Cheezels. Blackness and humour intermingled was a signature stamp of Luis’ writing.

The movie was bankrolled by several investors, but the main one was the South Australian Film Corporation (SAFC). Luis hired Esben Storm to direct, a young ‘enfant terrible’ director of the day who had stunned everyone by winning the AFI award with his film 27A which depicted the forced sectioning of alcoholics to mental asylums. I saw that movie, met up with Esben and realised that he was an inspired choice for Angel Gear. Luis never went anywhere near the mainstream. It was as if he had a powerful negative magnetic pole that wouldn’t let him connect with it. Even his ‘mainstream’ TV work had to be a kind of Buñuel movie snuck through in disguise.

The opening sequence of Angel Gear had to be shot on a certain day in April, a few months before the rest of the schedule. Esben’s inspiration was to shoot The Loner’s departure from the city at the Anzac Day Parade in Sydney. With 70mm cameras hidden around the buildings and in George Street I walked, with a backpack, towards Circular Quay against the huge human tide that was traveling in the opposite direction, so that when I reached somewhere around Hunter Street the last of the massed parading lines of military veterans disappeared from the frame and I walked on alone through a suddenly utterly deserted city.

The idea was pure genius, and with Mike Lake as 1st AD co-ordinating a large team in what was basically a guerrilla shoot, we got the whole sequence in the can.

What then happened was that a few weeks later, after a cut was made of the opening sequence, the SAFC, for bizarre and convoluted reasons which I won’t go into, pulled their funding, and the movie died, stillborn and without recourse to rescue.

Lyn and Luis had done what we are always told not to do and sunk everything they could borrow, using their house as collateral, into funding the movie. Contractual gobbledegook and bullshit stitched them up. They sold their house and moved into a motorhome. That was it. All they had. Apart, of course from their talent and life-force, which never diminished.

I was living in a small half terrace in Sydney when a Winnebago with a motorbike bolted on the back pulled up outside, and I helped Luis connect to our electricity. He and Lyn had come to start up again somehow, and they were going to rest for a few days. Luis proudly showed me around his new ‘abode’. He was pumped.

“This is fucking incredible! Who NEEDS a fucking house?! I fucking love this! No garden! No fucking rates! And we go wherever the fuck we like! Why didn’t we fucking think of this before?!”

From there, Lyn engineered a remarkable turnaround. Luis worked as a freelance writer, and Lyn was script editor and producer, a few years later joining up with Jim Davern (the original concept writer of Rush who had returned to Australia from England to first become head of drama at the ABC and then branch out on his own) with whom she created and was the lifeblood of the huge hit TV series A Country Practice.

They were back in a series of houses, although now in Sydney. Luis initially re-embraced the concept of living in a house (“It’s okay. I got frustrated and shot a fucking hole in the ceiling with my shotgun. But it was my fucking ceiling, and I fixed it.”). However there were things that I and other friends could easily see were not going to lead to ongoing harmony. When Luis and Lyn split up their young son Danny was on the scene, and the return of Luis’ aversion to the responsibility of children was not a big shock either to her or anyone else.

Luis spent much of the last 30-something years of his life in a gradual retreat from the necessities of life. He never abandoned life or became a recluse – he just moved further into ever more remote bush locations where his ‘needs’ were less. He kept on ‘doing things’ wherever he was was. He became a big part of the country communities in which he lived. And he painted again – more and more until he was having exhibitions in Collingwood.

When it seemed he had written his last script commissioned by other people, he kept writing his own. He read and rated scripts that were submitted to Film Victoria, and it’s a shame that his more eccentric recommendations were not supported by other more conservative assessors, although this role did lead to him becoming a script editor on the feature film 100 Bloody Acres, and in turn close friends with the film’s writer/directors, Colin and Cameron Cairnes.

In his late 70s and 80s, Luis made a trilogy of completely independent, self-funded feature films. He had a script, a camera, and teams of unpaid locals who loved their ‘resident movie-man’ and worked freely with him as actors, extras, caterers and production staff. He was granted any location he asked for.

I had a fabulous time being in two of Luis’ movies made in the Colac region of Victoria. Amateur and home-made they certainly were, but it was the ‘process’ that kept Luis going. Me too. We sat together eating the Spanish omelette that Luis made with love and care, and discussed the days work while planning the next, and the main thought in our heads was: ‘We’re doing all this without a boss!’ Luis was ecstatic.

“Yes! No fucking producer! I can change my mind any time I fucking want! It might be shit, but it’s MY fucking shit!”

I couldn’t help sharing the feeling of wellbeing and enthusiasm Luis inspired. That was the good side of him. We all have our darker side and he had his, but about so many things to do with freedom, creative and otherwise, he was right. I would be thinking: ‘Maybe if we had a sound recordist it would help. Or a first AD to keep things organised.’ And then I would realise something: there would be a DVD and it would be cherished by all the locals who had jumped in to help. They knew nothing about how to make a movie and they probably wouldn’t have learned much either, but it all comes back again to the ‘process’. That was organic. Luis’ camera operating was mostly pretty workmanlike and, yes the sound was really shite. It will never cut. Not in the normal way anyway.

But what if more things were added to make it ‘better’. A crew? A production office? Where do you stop? One thing always begets another and then you get away from that freedom. A freedom you’ll never have working on something formulaic.

There was no formula to Luis Bayonas. Thank fucking fuck for that.