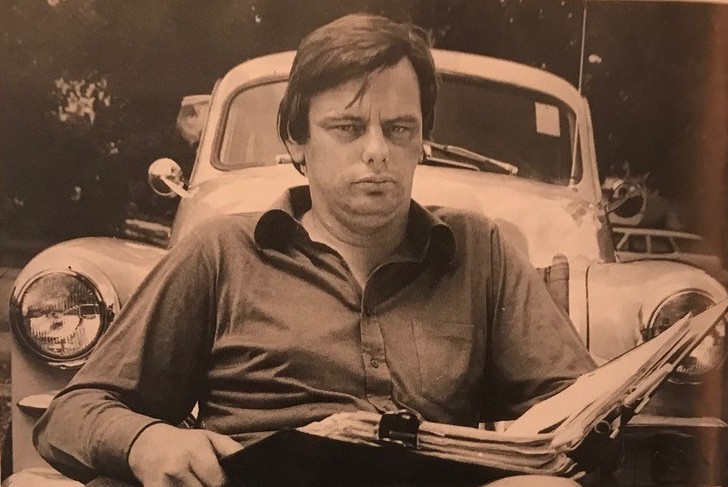

Michael Thornhill, the filmmaker behind ’70s features Between Wars and FJ Holden, died late last month, aged 80. Here friend Stephen Wallace reflects on his legacy.

Michael Thornhill was, and is, an important Australian filmmaker, film critic, film and TV producer as well as a rather contradictory character. To my eyes he was both a poet of the cinema, a political loudmouth sitting yelling at me in the corner of a pub, and a loyal friend. He was talented, intelligent and verbose; a much loved personality.

As a director the ground he covered breathed working class underdog, intelligentsia rebel, sexual underworld observer and criminal underworld storyteller. His film tastes, as he said himself, were “catholic”. Though not always commercially successful, his films were unreservedly down to earth Australian, something that other filmmakers didn’t achieve because it’s either in your bones or it’s not.

His major features, Between Wars (1974) and FJ Holden (1977) were groundbreaking ventures in the early days of Australian cinema. His short film The American Poet’s Visit (1969) was the best short film ever made from a Frank Moorhouse story. His influence on the Australian film industry was huge, especially when he was a generous and astute executive at the New South Wales Film Corporation (later the NSWFTO) where he, David Roe and Jenny Woods were instrumental in funding films like My Brilliant Career, Bliss, Stir, Newsfront and many others.

Michael was born in Paddington on March 29, 1941 to Mr and Mrs Frank Thornhill. His mother was English, she came from Sale in Cheshire. The family moved to Tasmania where she died when he was four. Michael lived with his father till his late teens when, without doing the leaving certificate and with nothing but a passion for film in his head, he travelled to Melbourne.

There he met filmmaker Tim Burstall, who encouraged his film interest. He then moved to Edgecliff, Sydney to live with his aunt, artist Dorothy Thornhill and her husband, artist Douglas Dundas. Dorothy became his surrogate mother who loved, spoiled and supported him financially. She was a very fine artist herself and Michael adored her.

Michael’s first job was as an ABC projectionist. Producer Richard Brennan remembers meeting him at the ABC in 1959 when he was a rake-thin 19.

In the early 1960s he started attending the WEA film study group run by Ian Klava (then director of the Sydney Film Festival). There he met writer Frank Moorhouse, a fellow film enthusiast who worked at the WEA and film teacher John Flaus.

Gillian Burnett and Sandra Grimes, both runaway, rebel young girls then, were working in the WEA library at the time. They invited Michael, who had become good friends with Frank, to come to the Newcastle Hotel with them on Friday nights.

This was his introduction to the “Push” (or “baby Push” as film producer Margaret Fink describes them). The “baby Push” was a loose group of intellectuals, would-be writers and artists developed from professor John Anderson’s original Libertarian Society of the 1950s. They met at the Royal George Hotel in Sussex Street or the Newcastle Hotel in George Street. After the six o’clock closing they would often go to Lorenzini’s wine bar in Elizabeth Street.

This introduced Michael to a like-minded, mildly seditious young underclass of male and female artists and intellectuals. It strengthened his radical ideas and secured his relationship with Frank Moorhouse.

He began to write articles for the WEA’s Film Digest and in 1965 he and Ken Quinnell, who he met at the Newcastle, started publishing the Sydney Cinema Journal. He also worked as a film editor.

He became a film critic for The Australian and The Sydney Morning Herald between 1969 and 1973. Richard Victor Hall invited him to the “literati“ Friday luncheons at Tony Bilson’s Bon Gout.

In 1969 he made The American Poet’s Visit, based on a short story by Moorhouse and co-written with Ken Quinnell. Filmed over two weekends by Russell Boyd in Bill Bonney’s house where the original event had taken place, it had a miniscule self-raised budget of $900. Michael kept as close as he could to the spirit of Frank’s writing and the result is a wonderfully truthful, chaotic document of those times and those people. It launched Michael’s directing career.

In 1970 the Australian government starting funding short films and he followed up with The Girl from the Family of Man in 1970 (budget $4,000) and The Machine Gun in 1971 (budget $5,000). After two documentaries for the Commonwealth Film Unit (CFU) in 1974 he made the feature Between Wars, written by Moorhouse. It starred Corin Redgrave and was Australia’s first serious political film, examining Sydney society between the wars through the eyes of a psychiatrist. It was a bold, elegiac venture. He followed this with FJ Holden in 1977, a film set in Bankstown, an apparently ”formless study of a group of kids living in Sydney Western suburbs”. Written by Terry Larson, it was not the usual “ocker comedy” or a “gentle romance” but a “value free look” at the lives of these kids. It had a mixed reception, was roughly directed (Michael was occasionally insecure with film grammar) but was an example of Michael’s inherent poetic understanding of the core of Australian life.

In 1979 he directed The Journalist and in 1983 he produced the excellent documentary Who Killed Baby Azaria (1983) with Errol Sullivan. His last film was The Everlasting Secret Family (1988.)

He was a staunch supporter of the Australian Directors Guild, of which he was a founding member. He never married but his most sustaining relationship was with writer Thea Welsh, who predeceased him.

The memory of his work, both in directing and writing, the power of his personality and ideas, still plays strongly into our industry. His tenacity and poetic outlook is an inspiration for Australian filmmakers. I’m sorry we never told him that.

Isolated by Covid rules he died peacefully under care at St Basils Aged Care in Annandale on January 22.