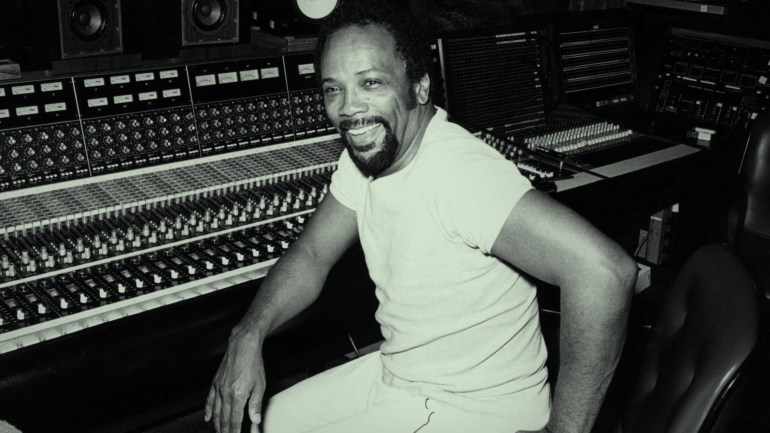

‘Quincy’.

Australian Al Hicks (‘Keep On Keepin’ On’) is the co-director of Netflix documentary ‘Quincy’, which profiles legendary music producer and composer Quincy Jones’ life and career, working with the likes of Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson. One of the speaker’s at this week’s Australian International Documentary Conference (AIDC), Hicks tells Jackie Keast how he made the film together with Quincy’s daughter, actress Rashida Jones.

You obviously knew Quincy Jones; he helped produce your first film. How did you come to make this documentary?

It’s a little bit complicated. When I was 18 I moved to New York to study jazz; I’m a drummer. During that time I met a gentleman named Clark Terry and we became really good friends. He took me under his wing and I eventually started playing drums in his band.

For a bit of context, Clark Terry was a trumpet player from the Count Basie band and the Duke Ellington band, who also taught Miles Davis and Quincy Jones trumpet. I’d been playing in his band for a long time, he was getting older and I had this feeling that this history was just going to disappear. I spoke to a mate of mine Adam Hart, who’s a cinematographer, about trying to document Clark. We ended up making the film Keep on Keepin’ On which is about Clark Terry mentoring a young blind piano player named Justin Kauflin.

Quincy just walked into that movie. He came to visit Clark one day while we were shooting. He perked up and was very inquisitive, trying to figure out who these Aussie guys were hanging with his teacher. Once he found out that I was also Clark’s student, we formed a bond and then he came onto that project. During that time I also met Rashida Jones, who is Quincy’s daughter. She was actually trying to start up a Quincy film. She had a 5D camera, saw our team filming and came up and asked some questions; she was trying to figure out some settings. We became really good mates and then she came and asked if I’d co-direct the movie Quincy about her father.

What was it like working with her? Obviously she gives you insider access to Quincy, and would have a very personal perspective.

It was brilliant. We had a wonderful time. The story of Quincy is so huge and broad that we really did need two people to split it up, and we both brought different perspectives to it. I grew up with Quincy’s music; I’ve got that outsider perspective of Quincy, and the musical perspective. I’m a total nerd for all his music. Then she’s his daughter, so she knows him like nobody does and has an emotional gauge for how we’re representing him and what his personality is really like. It also enabled a lot of harder truths to be in the film. Quincy nearly passes away a couple of times in the movie, and you’re right there with him in the hospital. You can only achieve that with the trust that comes within a family.

We had also already developed a lot of trust, me and producer Paula DuPré Pesmen, from working with Quincy on Keep On Keepin’ On. So he just said to Rashida and me, “I don’t even want to see it, just make it and I’ll see it when it’s done. I trust you guys.”

So you had creative freedom.

There’s the stress of having to show him at some point, but creative freedom all the way. We travelled with him; I was on the road with Quincy for a bit over three years. We filmed 850 hours of

current day footage with him in 25 different countries, and then we found 2,000 hours of footage in his archives. You really get to know somebody when shooting them for that long.

Before you began the film did you know what story you wanted to tell?

Fortunately Rashida and I are very creatively aligned. That’s probably why it was such a positive and beautiful experience making the film. But we set some parameters. We decided we didn’t want any talking heads in that film.

It a bit more challenging, but it means that visually the story is moving forward all the time. There are a few movies that have done it in the past really effectively like the movie Senna about the life of Ayrton Senna. The movie Amy does it really well as well.

We wanted to keep it under two hours. We wanted it to be a relationship between the present and the past, [for the audience] to able to tell his past is informing the present day and vice versa. [We were trying] to find moments that can take us back into the past.

When you have that tremendous amount of footage, how do you begin the editing process? How do you work out where the story is?

We were organising whilst shooting. Quincy’s got an archive in his basement and so if we weren’t shooting, we were in the archive, sorting through it, scanning photos, transferring old VHS tapes. That took about a year of work [and we were] in his archive every day that weren’t on the road with him. Once we got through that, Rashida and I went up to Quincy and told him, “Great news, we got through the archive. We’re finished!” He’s like, ‘Oh that’s beautiful. But the vault is where all the good stuff is. You got to go to the vault.” We couldn’t believe it when we heard that. That meant another eight months of work in this vault that was offsite. That’s where we found all the Super 8 footage from his past, all the Frank Sinatra interviews, the Ray Charles interviews, him playing with Duke Ellington on a TV special in the ‘70s. All this amazing music, these masters that we were able to pull and use. Then we did one year of prep while we were shooting, watching every single bit of footage that we had.

We were working through it in Premiere. You can put markers into a day of footage and you can export those markers into a spreadsheet. So say it was an eight hour shoot day, we were able to watch through all of that footage and if he spoke about Frank Sinatra, we’d leave a marker that says ‘Frank Sinatra’, if he spoke about his mother, say ‘his mother’ etc. Once we got through all of that material we were able to export all the markers and have a master spreadsheet. Then we would get an assistant to search for Frank Sinatra, and using the spreadsheet find any time he ever spoke about Frank Sinatra and put it into one sequence. Those sequences would end up being between 20 to 25 hours long. We’d work through that, cull that down, get it down to 15 hours, get it down to 10 hours, five hours, one hour. Once we had it to 20 minutes, we’d sit down with the editor and pull it into a three or four minute scene. That way of reduction, by the time you get to 20 minutes, you totally know what the scene is. You can really feel your way through it and the scenes come together quite quickly – if you’ve done the prep work and if you haven’t died in the process. (laughs)

When approaching a documentary like this and your previous film, the music is a character in and of itself. How did you approach that here, especially because with Quincy there are seven decades worth of music to choose from?

On Keep on Keeping On’, over the years studying with Clark Terry, we would just always end up talking about his music or listening to his old records. He would tell me his favourite solos on different songs, or what his favourite band was. I always kept a list of his favourite music that he had been a part of. So when it came to putting music into that film, I just had this list of 150 songs that I knew that Clark would want in his film.

With Quincy, I knew his music, but I had no idea of the breadth. Clark Terry, he had 200 original songs. Quincy Jones has 3,000 songs.

There’s a gentleman Jasper Leak who’s another Australian, he used to play bass in Clark Terry’s band with me. I ended up approaching him and asking if he’d come on as a music supervisor. While we were going through the footage, he was going through all of Quincy’s music. All 3,000 songs, cataloguing them, listening to them and making spreadsheets that could lead you to different parts of different songs and find the really amazing bits of music that he’d made. Again it’s just this nerdy stuff that’s so helpful creatively. He created a spreadsheet; you could search things by moods like ‘melancholy’, ‘happy’, ‘sad’ and also by instrumentation. Say if I wanted something that was just percussion, he could search ‘percussion’ and there’d be 20 tracks that come up.

We’d get a scene into a workable space and go to Jasper and say “It’s Chicago, we need something dark, bluesy, something that’s sort of gripping and solemn.” He’d be able to say “Here are 15 options, but I think this one’s probably your best bet”. Nine times out of 10 he’d be spot on.

We wanted to tell a story musically, so you could just close your eyes and just listen to the music through the movie and it would take you on a journey.

When you’re working with archival footage and music, the first thing that comes to mind is getting the rights to use it. Was there ever difficulty on either of your films with that?

Always. But the way that I like to go about it is just shoot for the stars. Put the music in that you really want. There’s no use making a creative decision based on the possibility that it might not work, or thinking “There’s no way we could use this song. So let’s not use it and we’ll use something else.” You never know, you might be able to reach out to the songwriter and they would love to be involved. Obviously the team that has to deal with the licensing doesn’t appreciate that style of doing things. But yeah, I just put in what I think is perfect and best for the scene. A lot of the time it comes back and they’re like “You definitely can’t license that”. But it sets the tone of the scene and then you can replace it with something that still works and maybe works even better. Licensing troubles are something that force creative decisions. A lot of times it makes it better in a weird way, because you would never have made that decision in the first place.

How do you think your background as a musician informs your approach to filmmaking?

There are so many parallels between music and filmmaking. When you’re pulling together a scene, it’s so similar to a song. You need a beginning, middle and end, you need a turning point. If you’re putting together an album, you want the songs to move from song to song – you don’t want to put three ballads next to each other. You want to keep momentum and a story arc with each song lyrically or musically. You’re doing the same thing when you’re when you’re putting a scene together.

I’m a drummer and editing is so much about pacing and rhythm. There are things that are drilled into you when studying instruments and how to keep time; you can tell when something’s dragging. That’s an asset in the editing room. There’s nothing worse than a non-musical editor. An editor that understands music or the feeling of music can make decisions that they can’t even explain that are just better. On this film we are able to work with an amazing editor, Andy McAllister, who’s also a musician. We had a language where I could say, “Hey man, the first bar of the bridge, on the e of second beat, can you make the cut?” and he could just do it. Trying to explain that to an editor that doesn’t understand music, it’d take you 10 minutes to get to get the cut exactly where you would like it.

Music and filmmaking go hand-in-hand; I think they use a similar part of your brain. The best collaborators I’ve had have also been musicians. On this film, Rashida’s a musician, one of the editors was a musician, Jasper is a musician, the mixer is also really accomplished musician. I’ll end up probably doing that for the rest of my career, surrounding myself with musical filmmakers.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a lot of narrative stuff. I’m working on a short which is a little Australian comedy and I’ll hopefully be shooting that in the middle of the year. I’m working on a pilot for a TV as well, writing that. A few ad things are coming up. Then I’ve got a tour that that I’m going to be doing in Australia this year, playing music. So things are busy, but no documentary stuff right now. My first movie took me five years. The second one took me four. Every time you commit to a feature length documentary it’s like committing to a college degree. You have to choose wisely if you’re going to be doing a movie and make sure you’re doing it for the right reasons. A decade can just fly by and if it’s not something that you really loved it’s a drag.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Al Hicks will present a masterclass on music documentary at AIDC later today. Quincy is on Netflix.

An original version of this article appears in the print edition of IF Magazine #187 February-March.